Betting on Regime Change

Someone made a fortune betting on Maduro's capture. It exemplifies how prediction markets are reducing world events to nothing more than a casino wager.

“Kalshi is replacing debate, subjectivity, and talk with markets, accuracy, and truth” - Tarek Mansour, CEO of Kalshi (2025)

“[money] replaced the subjective appreciation of objects, goods, services, with an objective evaluation of them in terms of their monetary value, and in the process had often debased them.” - Susan Strange, Casino Capitalism (1986)

Early Saturday morning, U.S. special forces carried out a military operation to capture Venezuela’s strongman leader, Nicolás Maduro. Planning such a complex undertaking is no easy task. It reportedly involved the CIA, NSA, DEA, NGA, Navy, Air Force, Cyber Command, and the Space Command.1 This would suggest there were hundreds of people with advance knowledge of the operation and its precise timing. If you were one of those people, what would you do with that information? In Trump’s America, there is only one logical answer to this question: profit.

And that is precisely what many suspect has happened. Following news of Maduro’s capture, internet sleuths noticed that a single individual made more than $400,000 by correctly betting on the timing of Maduro’s ousting. That individual was placing their bets on Polymarket. Polymarket is the world’s largest prediction market, where you can gamble on sports, monetary policy, and other important events like whether Bill Clinton will get divorced by June 30th (6% chance).2

The individual in question — 0x31a56e9e690c621ed21de08cb559e9524cdb8ed9 — created their account approximately one week before the operation. They proceeded to place a series of bets on regime change in Venezuela. No bets were placed on any other topics (not even Bill Clinton’s divorce). Their collective gambles amounted to about $34,000, resulting in almost $410,000 in profit. Not bad for a brand new user with no prior experience using the platform.

The internet, as it often does, has theories. Many believe this is a member of Trump’s inner circle. Others have hypothesized that a Venezuelan informant is trading on their own subterfuge. Or perhaps it was just an intern at the NSA, plugging in their bets on Polymarket with Cheeto-stained fingers. Regardless, there is a widespread belief that what we are seeing here is insider trading. An attempt by some individual to illegally profit from their advance knowledge of the Venezuelan operation.3

None of us can truly know the answer. Except, perhaps, Polymarket. And, indeed, one would think that a prediction market should easily be able to see who is placing bets on their own platform. But it’s actually more complicated. Polymarket was approved to operate as a futures exchange in 2025, and that carries obligations to perform Know-your-customer (KYC) checks.4 Those rules largely do not apply, however, if you are placing bets from jurisdictions without such regulatory requirements.5 This creates obvious opportunities to trade semi-anonymously through VPNs.6

But there is a much bigger issue at play here. Prediction markets like Polymarket and Kalshi have rapidly arisen as arbiters of probabilities. Kalshi has struck deals with CNN and CNBC to be their “official prediction market partner,” ensuring that every story is accompanied by betting odds. This is not just America’s latest descent into the muck and the mire of casino capitalism. It is also the pure commodification of world events, one that alters our collective perception of reality while creating perverse incentives for those in a position to move the needle.

Truth Discovery

Platforms like Kalshi are certainly not the first markets to make it possible to bet on political outcomes. Commodity traders are constantly trying to price in the possibility of terrorism, regime change, and other geopolitical risks.7 And nothing moves stock markets quite like interest rate decisions. But this type of trading is an indirect bet on political outcomes. It is an attempt to guess how those outcomes will impact financial instruments, whether it be shares in Novartis or lard futures.

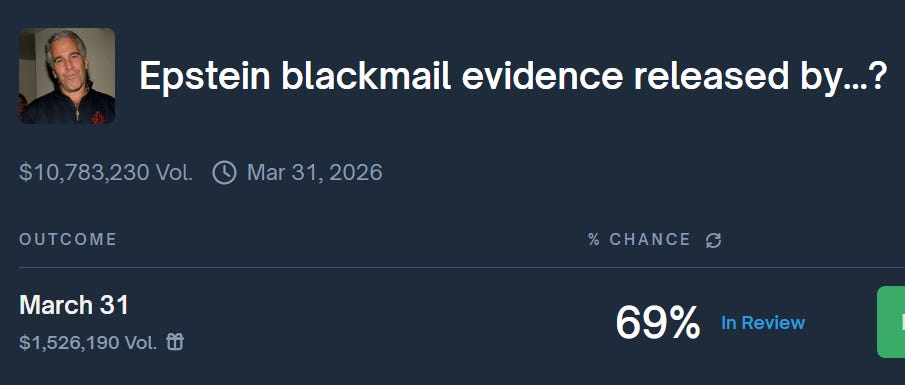

Prediction markets, in contrast, facilitate a direct bet. There is no intellectual exercise here about how elections in Vietnam will impact textile prices. It is simply a gamble on the political outcome itself. And those bets are not subtle:

Proponents of prediction markets contend that these types of bets serve an important social function: price discovery. This is the idea that the ‘true’ price of any one asset is determined by buyers and sellers interacting in markets. But when it comes to political events, what we are really talking about is truth discovery. Platforms like Kalshi tell us they are bringing together the collective knowledge of many individuals to formulate more precise predictions. It is a concept rooted in Friedrich Hayek’s vision of markets as the ultimate form of social organization:

We must look at the price system as such a mechanism for communicating information…in a system where the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coordinate the separate actions of different people…

…The whole acts as one market, not because any of its members survey the whole field, but because their limited individual fields of vision sufficiently overlap so that through many intermediaries the relevant information is communicated to all…8

We could also call this the Pluribus model. And it is one that major industry players believe is the key to prediction. Polymarket CEO Shayne Coplan, for example, claims that prediction markets are “the most accurate thing we have as mankind right now, until someone else creates some sort of a super crystal ball.”9 Former Acting Chair of the CFTC Caroline D. Pham is equally optimistic: “Prediction markets are an important new frontier in harnessing the power of markets to assess sentiment to determine probabilities that can bring truth to the Information Age.”10

Gatekeepers of Reality

But what is the social utility of predicting Bill Clinton’s divorce? What do we gain from collectively guessing whether Taylor Swift will be pregnant in 2026?11 This points to a major problem with the truth discovery thesis. While the market mechanism may be democratic, the selection of bet-worthy events is not. It is Kalshi and Polymarket that determine what truths are worth predicting.12

These platforms also determine the contours of truth. For every bet, there is a specific explanation of what qualifies. Take, for example, Polymarket’s rules for “Will China invade Taiwan by end of 2026?”:

This market will resolve to "Yes" if China commences a military offensive intended to establish control over any portion of the Republic of China (Taiwan) by December 31, 2026, 11:59 PM ET. Otherwise, this market will resolve to "No".

Territory under the administration of the Republic of China including any inhabited islands will qualify, however uninhabited islands will not qualify.

The resolution source for this market will be official confirmation by China, Taiwan, the United Nations, or any permanent member of the UN Security Council, however a consensus of credible reporting will also be used.

This is a minefield! How does Polymarket determine China’s intentions? What exactly constitutes “control”? What will Polymarket do if the “consensus of credible reporting” (who’s credible?) contradicts France’s statements?

The German sociologist Georg Simmel summarized this problem way back in the 19th century. Simmel was not a Marxist. But he was skeptical about whether money had a positive impact on society. Specifically, he was concerned that currency reduced the complexities of reality to a simple quantitative measure. As Susan Strange summarized in her 1987 book, Casino Capitalism:

[money] replaced the subjective appreciation of objects, goods, services, with an objective valuation of them in terms of their monetary value, and in the process had often debased them. It quantified, as he put it, the qualitative. It equalized what was essentially unequal and not truly to be compared…it also dehumanized the relationships and made them more mechanical, putting people, as we would say, at arms’ length from each other.13

I’m not so sure that money itself is the problem. And I like markets! I just published a paper proposing a market for financial crime bounty hunters. But Simmel’s theory is spot on when it comes to political prediction. The binary contracts offered by these platforms are reducing the irreducible. They are squeezing complex events into the tight jeans of a single quantitative measure. This is very dangerous for our collective understanding of reality. And it creates obvious incentives for powerful figures to profiteer by betting on their own actions.

The Market for Nihilism

But perhaps the saddest outcome is the nihilism. Trump’s attacks on Venezuela should arouse strong feelings; it should arouse strong debate. So too should Stephen Miller’s comments that the U.S. should invade Greenland simply because it can. Regardless of how you feel, you should feel something. But that is not the promise of prediction markets. As Kalshi’s CEO summarized, “Kalshi is replacing debate, subjectivity, and talk with markets, accuracy, and truth.”

Reducing Trump’s potential invasion of a NATO ally to a binary event contract is not providing “truth.” It is, instead, commodifying reality. It is transforming an extremely serious possibility into a parlor game. And it is providing us with an excuse to shut off our minds. Developing an opinion about the morality of American imperialism is hard work. It requires thinking, debate, and self-doubt. But prediction markets allow you to forget all these complexities. Their message: it’s all just a game. Another reality TV show with an over/under. Pop a Xanax, order some pizza, and pull out your phone to place some bets on the future of Gaza.

It is part and parcel of America’s descent into casino capitalism. In a fantastic podcast series, Michael Lewis documents how the legalization of sports betting has unleashed an epidemic of gambling addiction. We have also previously discussed the transition of stock markets to 24/7 trading. Political prediction markets are the latest example of this trend. There are some forces pushing back. Congressman Ritchie Torres (D-NY) is reportedly considering new legislation to prohibit public officials from participating in prediction markets.14 But will he be able to muster a sufficient majority to overcome Trump’s inevitable veto? I wouldn’t bet on it.

This has a very specific meaning when it comes to Polymarket bets. Polymarket is a registered Designated Contract Market (DCM) that facilitates trading in what the CFTC calls “event contracts.” In commodity markets, insider trading is legal unless the information was “misappropriated” in violation of a duty of care. The STOCK act basically specifies that government officials have a duty of care to not profit from inside information obtained as a result of their position. So a senior member of Trump’s cabinet, for example, would almost certainly be misappropriating inside information if they placed bets on Polymarket based on their advance knowledge of a U.S. military operation.

But it doesn’t guarantee anonymity. If you fund your account through Visa, for example, your trades can be connected to you through the KYC performed by Visa when you first opened an account. And if you use crypto, those transactions can still be traced through public blockchain records. Nevertheless, the careful criminal could navigate these narrow pathways to profit and move money very quickly.

This is related to a line of research on how markets are not self-organizing but rather very much governed as institutions. See e.g. Merchants against the bankers: the financialization of a commodity market.

This is very good. I listened to most of the Michael Lewis series, which as you say, is excellent. The world of online gambling, and the harms it causes, deserves a great deal more attention. There was a casino across from my husband’s office in Hull PQ. They held some meetings there, and my husband got chatting to one of the security guards about his work. He said he enjoyed it except for the suicides that occurred at least once a month in the parking lot. Several years later my husband was in charge of an engineering school, and gambling addiction was not uncommon among the young male students. They were able to direct them into treatment programs and financial counselling. This was before the advent of online gambling. I shudder to think how many people are drawn into gambling addiction today.