China and the Intangible Transfer of Technology

The U.S. and its allies want to block the export of sensitive software to China. But how do you stop the unstoppable?

Programing Note: False Positive now has more than 100 subscribers! Thank you to everyone who has taken the time to read, comment, and share.

During the first week of December 2023, a Google employee — let’s call them Jerry — scanned their ID badge to enter the company’s California offices. But Jerry was not just scanning his own badge. He was also scanning the badge of a co-worker, one who had asked him to make it appear as if he was in the office. This is understandable. We all want to play hooky sometimes. “Hey Jerry,” you might say, “my buddy Zane has a house in Lake Tahoe and just invited me out for a week of Après-ski. Mind scanning my badge a couple of times while I’m gone? I’ll buy you a beer!”

But Jerry’s co-worker was not Après-skiing in Lake Tahoe.1 According to a federal grand jury, the co-worker — Linwei Ding — was actually in China carrying some of Google’s most sensitive trade secrets.2 Over the course of a few months, Ding, a software engineer working on Google’s supercomputer datacenters, uploaded some very proprietary information to his personal Cloud account.3 This allegedly included software design specifications used to power some of Google’s most advanced applications of artificial intelligence. In the meantime, Ding was creating his own start-up in Shanghai which would, you guessed it: develop a software platform to train AI models powered by supercomputing. He made little effort to hide this copycat plan when texting his new employees:

…we have experience with Google’s ten-thousand-card computational power platform; we just need to replicate and upgrade it and then further develop a computational power platform suited to China’s national conditions.4

This is pretty common in the commercial world. Employees of banks and hedge funds, for instance, are often caught trying to steal the proprietary code which powers their trading algorithms.5 There are also regular disputes over “trade secrets,” whose legal definition expands beyond code to a more complex array of commercially valuable knowledge.6 Trading giant Citadel, for example, is currently suing two former staff who left the firm to create a crypto start-up in Switzerland.7 Citadel alleges that the pair stole not just trading techniques, but also the more vague categories of “business plans and business strategies…”8

But the Linwei Ding case is different. This is not just some commercial dispute about intellectual property. It is, more importantly, a matter of national security. The DOJ does not claim that Ding was working for the Chinese state. But Attorney General Merrick Garland was clear about the risks:

The Justice Department will not tolerate the theft of artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies that could put our national security at risk…We will fiercely protect sensitive technologies developed in America from falling into the hands of those who should not have them.9

It does not take a security clearance to guess that “those who should not have them” includes, first and foremost, the People’s Republic of China. The U.S. and China are engaged in a global technological arms race, one playing out in everything from AI to telecommunications infrastructure.10 Western powers are engaged in offensive strategies to stay ahead, exemplified by recent efforts to subsidize the production of advanced microchips in friendly territories11 Equally important, however, are their defensive strategies. Namely, strategies to block the export of critical technologies to China and other adversaries. These include new controls on the export of software, technical information, and other “intangible” assets.12

This is easier said than done. Tracking tangible goods like missiles or high-precision jig grinders is already a hugely complex task. But at least there are material components which need to be transported, creating opportunities to detect smuggling and disrupt its delivery. Intangible assets are trickier. They are, in essence, computer files which can travel across borders with the click of a button. Email, Cloud, Tor…preventing such transfers is like trying to catch water with your hands. How do you stop that? How, in other words, do you curb the export of knowledge?

The Porcelain Thief

In 1712, Father François Xavier d'Entrecolles wrote a groundbreaking letter to his Jesuit superiors in Paris. After spending years in China, Father François had uncovered the secrets of Chinese porcelain production.13 Such porcelain was, at the time, in high demand amongst European elites, many of whom were willing to spend considerable sums on a product exclusively made in China. European ceramic makers had tried but failed to replicate these products. The reason was simple: Chinese producers retained exclusive access to the ancient secrets of their craft.

That was all about to change. But the French Jesuit hierarchy was not satisfied with Father François’ initial letter. They informed him that it contained insufficient details to replicate the production of porcelain in France, encouraging him to collect more information and report back. As Robert Finlay writes in his book, The Pilgrim Art, this was an early form of stealing trade secrets:

[d'Entrecolles’] superiors plainly sent him to Jingdezhen on a mission of industrial espionage, no doubt with the pious hope he would save some souls along the way. His letters represent one of the earliest and most calculated cases of an effort to implement mercantilist economic strategies of technology transfer, import substitution, and product innovation.14

Father François would spend another 10 years studying the Chinese process before delivering his second letter. His insights would spur a wave of information-gathering missions, eventually leading to the replication of Chinese porcelain techniques in Europe (exemplified by Delft’s blue and white pottery). But even after a decade of further research, certain secrets remained elusive. Father François had discovered, for example, that red glaze was created by grinding copper and stone with the “urine of a young man and some pe-yeou oil.”15 But he could not obtain the exact proportion of the ingredients: “the secret is well-kept and not let out.”16

Chinese porcelain makers would not be the last industry to worry about the loss of trade secrets to foreign powers. Approximately 250 years later, in a historical reversal of sorts, the U.S. Department of Defense assembled government experts and business representatives to discuss how to prevent the export of “critical technologies” to Communist countries.17 Everybody was there: Texas Instruments, General Electric, Xerox, Northrop, Lockheed, Boeing, the CIA…the collective might of the American military-industrial complex. Their discussions would set the stage for the modern day battle over the intangible transfer of technology.

The Irreversible Decision

Remarkably, the DoD report, released in 1976 — primetime Cold War — starts with a quote by Vladimir Lenin:

The inherent contradiction of capitalism is that it develops rather than exploits the world. The capitalistic economy plants the seeds of its own destruction in that it diffuses technology and industry, thereby undermining its own position. It raises up against itself foreign competitors which have lower wages and standards of living and can outperform it in world markets.18

The placement of this quote, at that time, in this report, is so wonderfully weird and open to interpretation. “You know what,” I imagine an intern saying to another intern, “this Lenin guy was kind of on to something…let’s start with that.”

It would appear that the committees did, in fact, agree with Lenin that diffusing technology abroad could undermine American security. “The release of know-how,” the introduction summarizes, “is an irreversible decision. Once released, it can neither be taken back nor controlled.”19 And, indeed, the committees repeatedly emphasize that preventing the transfer of ‘know-how’ is often more important than preventing the actual outputs of that knowledge. The problem was how. Export controls were already in place, but one committee concluded that they offered little deterrence effect when it came to knowledge transfers.20

Particularly problematic were these pesky new computers. Committee members were concerned that their export to the Soviet Union would create a whole new generation of dangerously computer-literate Russians:

….the widespread use of computers, even in commercial applications, enhances the ‘cultural’ preparedness of the Soviets to exploit advanced technology. It gives them vital experience in the use of advanced computers and software in the management of large and complex systems. The mere presence of large computer installations transfers know-how in software, and develops trained programmers, technicians, and other computer personnel. All of this can be redirected to strategic applications. Safeguards cannot affect this process.

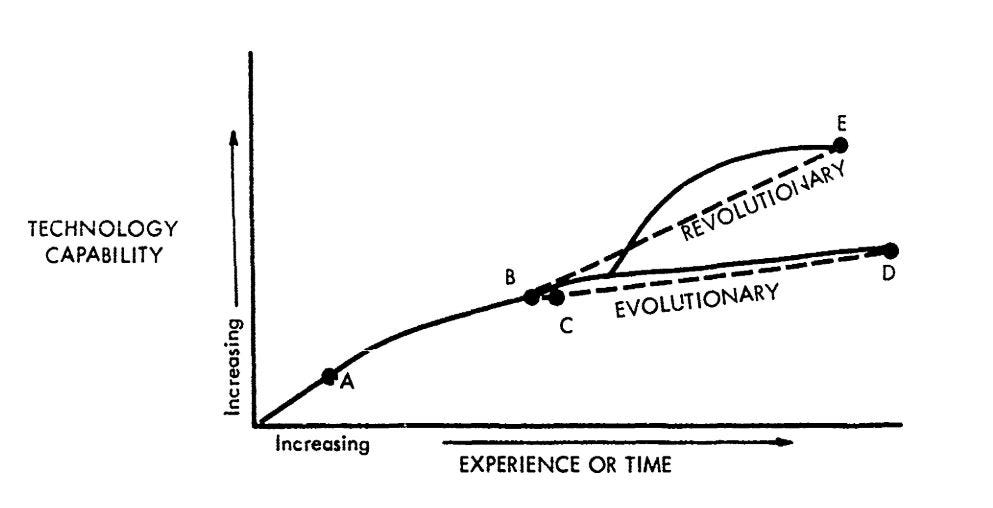

The report concludes that, to the extent possible, the U.S. should minimize the export of such “high velocity technology” which might allow Communist countries to obtain “revolutionary” gains.21 Such exports should, in other words, be cut off sometime between points A and B in the following graph:

But the committees did not delude themselves into thinking they could completely block the adoption of technical ‘know-how.’ The emphasis, instead, was to slow down adversaries and maintain the lead.22 The U.S. and its allies would do so by adding certain types of software and data to the lists of controlled goods maintained by the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM).23 The COCOM was established after World War II to coordinate Allied Powers’ export controls against the Soviet Union and other Communist-curious states.24

A few decades later, however, the Clinton administration would substantially alter U.S. policy. Guided by the ideals of trade liberalization (and, perhaps, the business interests of Silicon Valley), Clinton relaxed controls on computer exports to China.25 In 1993, for example, the U.S. allowed China to purchase an $8 million supercomputer created by Cray Research in Seattle.26 This was a reversal of the Bush administration’s earlier decision to block such a sale and, reportedly, went against the advice of Defense and Energy Department officials.27 Clinton would also oversee the dissolvement of the COCOM. In recently declassified transcripts of a 1993 meeting with Russian President Boris Yeltsin, Clinton clearly expresses an interest in replacing or changing COCOM to promote free trade:

Clinton: On COCOM, of course this involves other countries, we will support a reorganization of COCOM for new business. We already have a long list of items we want to see liberalized -- machine tools, computers and telecommunications such as fiber optics. These are things you are interested in.

Yeltsin: It would be good if we could take part in this new organization.28

Russia would indeed join COCOM’s replacement, the Wassenaar Arrangement, named after the Dutch suburb in which it was founded. Like its predecessor, the Wassenaar Arrangement serves as a mechanism to coordinate export controls, including those pertaining to software and other “intangible” transfers. But the Clinton-led boom in trade liberalization had opened the floodgates to the international spread of ‘know-how,’ a decision U.S. officials once warned was irreversible.

Tracing the Untraceable

Fast-forward to present day, and the trade dynamics between China and the West have yet again reversed. In direct contrast to the Clinton era, the Biden Administration is explicitly seeking to knee-cap China’s technological development. Key to these efforts are what one set of authors refer to as a “cascade” of export controls on semiconductors and other sensitive technologies.29 Biden has also issued an Executive Order designed to limit U.S. investments in semiconductors, quantum computing, and AI which may afford “intangible” benefits.30

But establishing restrictions is one thing. Enforcing them is another. How do you actually stop the transfer of software, data, and other intangible assets? One step is to review export license applications. Most countries require firms to obtain licenses before exporting certain sensitive goods. In the U.S., for example, you need a license to sell various forms of software abroad, including those used for cryptographic enabling/activation (5D002.b), unmanned submersible vehicles (8D999), and, of course, nucleic acid assembly (2D352).

The Bureau of Industry and Security, or BIS, has the unenviable task of reviewing every application made in America. In 2022, for example, the BIS received 4,555 applications for exports to China involving commodities, software, and technology, 71.4% of which were ultimately approved.31 The effectiveness of this process is highly dependent on the quality of the BIS’ data analysis tools. Unfortunately, however, those tools do not appear to be working very well. One think tank interviewed 50 current and former officials who “uniformly stated that BIS internal digital infrastructure and databases are in extremely poor shape.”32 There is, for example, a database containing billions of records of trade transactions which the BIS monitors. But the system is often non-responsive or crashing. This has Schrödinger's cat-like effects: if you enter the exact same query twice, you may get different results.33

More to the point, one does not need to apply for an export license in order to send sensitive software abroad. You could just…do it. The BIS, with its bronze-age IT tools, cannot monitor every email or file transfer. Thus it relies on private firms, universities, and other institutes to enforce export controls on its behalf. These organizations are the actual laboratories of intangible knowledge. And they are generally responsible for ensuring that knowledge does not fall into the “wrong” hands. Princeton, for example, has a fancy webpage dedicated to this topic, including a handy flowchart explaining when an export license may be necessary.

Generally, private firms and universities have strong incentives to fulfil these tasks as a method of protecting their intellectual property. That might entail invasive forms of corporate surveillance. Many companies track the location of their employees through their devices (including company cars) to monitor whether they are seeking to access sensitive data from unauthorized locations. Solutions have also been created to follow the movement of software, a process akin to implanting a tracking device in files to create a blockchain-like record of actions.34

But these solutions are far from perfect. Google was also performing surveillance on its employees when Linwei Ding booked a one-way flight to Beijing.35 But Ding found an astonishingly simple loophole. When he wanted to steal a file, he would copy and paste the code to Apple Notes, convert the Note to PDF, and then upload the PDF to his personal Cloud account.36 It was through this remarkably simple method — the same method one might use to save a crockpot recipe — that Ding transferred some of Google’s most sensitive trade secrets to China. In the end, the world’s most powerful tech company was no match for Apple Notes.

It is here, in these digital spaces, where the technological battle between the U.S. and China is truly occuring. In the 18th century, European missionaries had to spend years on the ground to engage in corporate espionage, gaining the trust of local porcelain manufacturers and observing their every step. But the tables have turned. It is now China which seeks to capture the secrets of the West. And the nature of those secrets has radically changed. The intangible assets China seeks — human knowledge in file form — are scattered across the globe. Western governments can, on paper, ban the export of that knowledge. But the actual implementation of those controls is largely out of their hands. Their success will, instead, be determined on thousands of separate digital battlefields, where private firms, universities, and other laboratories of knowledge fight to defend their intangible treasures.

Nor, to my knowledge, does he have a buddy named Zane.

As alleged in the DOJ’s March indictment. The identity of the co-worker who allegedly scanned his badge was kept anonymous.

As alleged by the Department of Justice.

Indictment, p. 6.

According to Winston & Strawn, the United States Patent and Trademark Office considers trade secrets a type of intellectual property referencing “the business ownership of a formula, pattern, compilation, program, device, method, technique, or process that provides a competitive edge.”

The internet archive hosts some of the initial court documents.

Amended compliant filed 7/21/23, p. 7. Lawyers representing Portofino Technologies, the defendant firm, counter that Citadel’s suit contains “baseless insinuations, calculated distortions, and outright falsehoods” designed to cynically squash competition. The vagueness of the concept of trade secrets was recently touched upon by Matt Levine in his Money Stuff column, Jane Street Wants Its Secrets Back. Levine covers another cases where it appears that an employee of Jane Street identified an exploitable market opportunity, left the firm for another hedge fund called Millennium, and began exploiting the same opportunity at Jane Street’s expense. The case raises complicated questions about whether such opportunities — which might be ascertainable through public sources — can ever constitute protected intellectual property.

DOJ announcement.

See, for example, Eva Dou, “Trump dreamt of a ‘Huawei killer.’ Biden is trying to unleash it.”

Not a lot of creativity in titles, however. The U.S. calls it the CHIPS and Science Act, whereas the EU calls it the…EU Chips Act.

I originally chose the cover art for this piece simply because it depicted Chinese trade. It later occurred to me that it would be interesting if the Chinese porcelain industry had export controls of its own, which led me, through a chaotic internet deep-dive, to the story of Father François Xavier d'Entrecolles. To top it all off, I discovered that Cara Giaimo covered the story of Father François in a review of Robert Finlay’s The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History while also making a connection to modern day controls on technology transfer to China! Just another example that everything really has been done before.

Finlay, The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History, p. 49.

The Second Letter from Père d'Entrecolles.

Ibid.

As political scientist Thane Gustafson write in a 1981 report for RAND, the U.S. concluded that “rather than construct impermeable barriers to the transfer of militarily significant technology, the aim of the control system should be to retard the flow so as to protect lead-times in the military areas in which the United States has a significant edge” (p. 4).

John F. McKenzie, Implementation of the Core List of Export Controls: Computer and Software Controls, 5 SOFTWARE L.J. 1 (1992).

Ibid.

See, e.g., ABC News, Clinton’s Gift to Silicon Valley, And China.

Elaine Sciolino, U.S. Will Allow Computer Sale To Court China.

Ibid.

Declassified Memorandum of Conversation.

Sujai Shivakumar, Charles Wessner, and Thomas Howell, Balancing the Ledger: Export Controls on U.S. Chip Technology to China.

BIS, Analysis of U.S. Trade with China, 2022, p. 10.

Gregory C. Allen, Emily Benson, and William Alan Reinsch, Improved Export Controls Enforcement Technology Needed for U.S. National Security, p. 10.

Ibid.

Indictment, p. 3.

Ibid.

Enjoyed this piece a lot! I wonder if the other component besides the transfer of intangibles is actually tech transfer via the movement of personnel/know-how…