FinCEN and the Data Dilemma

FinCEN received a record-breaking 4.6 million Suspicious Activity Reports in 2023. But is it really possible to process such volumes?

Combatting financial crime is all about information. Bank account numbers, letters of credit, beneficial ownership structure charts…these are the types of data points which form the basis of any successful investigation. Some of this information is public. You can, for example, go to the Mauritius Company Registrar and find basic incorporation data on Secret Empire Ltd.1 But most of the good stuff is not publicly available. It sits instead in the confidential databases of private companies, free from the prying eyes of most regulators and law enforcement agencies.2

These agencies have, however, developed certain workarounds. They can issue subpoenas for information, forcing private companies to cough up data on their customers. And, in some cases, they can set-up a wiretap to snoop on suspects’ emails and phone calls. But these steps occur after suspicions have already been developed. How do these agencies determine who to investigate in the first place? Where, in other words, do they get their leads?

When it comes to financial crime, one very important source is the Suspicious Activity Report.3 SARs, as they are more commonly referred to, are electronic reports which banks and other financial institutions are obligated to submit to regulators when they observe potentially suspicious client activity. Say, for instance, that you work at a bank and have a client who runs an all-cash beauty parlor. If they start making regular payments of $9,999 to an unknown account in Ciudad Juárez, you’re probably going to need to submit a SAR.4

These obligations are not unique to the U.S. Most countries now require financial institutions to submit SARs (or equivalent notifications) when they suspect clients may be engaged in money laundering or related crimes. These reports are sent to Financial Intelligence Units, or FIUs, government agencies responsible for analyzing SARs and making them available to law enforcement. Some FIUs have fun names, like FinCEN in the U.S., AUSTRAC in Australia, and Tracfin in France. Others are, well, more to-the-point, such as FIU-Netherlands.

This is a convenient arrangement for FIUs. They get to outsource the costs of frontline detection to the private sector, sipping coffee at their desks and waiting for the tips to roll-in. But you don’t want them to roll-in too fast. Government agencies, after all, have limited resources. What is the optimal number of daily tips per analyst? Three? Four? Perhaps, if we are being optimistic, we can assume each analyst can properly analyze, say, six tips per day.

But these are not quite the numbers faced by FinCEN. In their 2023 annual report released last week, the agency announced a new global record: 4.6 million SARs in one year.5 One might assume that FinCEN has substantial resources to deal with this avalanche of data. FinCEN is, after all, an integral component of U.S. national security, responsible for analyzing SARs to identify terrorist financing and efforts to evade economic sanctions. Surely such an important agency, facing such tremendous SAR volumes, must have thousands of staff? Try 300.

Doing More with Less

If we were to generously assume that half of FinCEN’s employees are fully dedicated to processing SARs (the agency, mind you, has many other responsibilities), the 2023 numbers would equate to 30,666 yearly reports per employee.6 To keep pace, each analyst — assuming they work 260 days per year — would need to closely analyze at least 118 reports per day. No bathroom breaks!

Obviously this is not realistic. And, if we look at historical data, FinCEN’s staffing and resources have not kept pace with the growth in SARs. To facilitate comparison, I calculated, on a year-by-year basis, the percentage change in FinCEN’s SARs, budget, and staff relative to 2014 (see below).7 Over an eight-year period, the total number of SARs received by FinCEN has increased by a remarkable 124% (from approximately 1.9 million in 2014 to 4.3 million in 2022). If we were to include FinCEN’s recently reported total for 2023, that growth rate jumps to 139%.

We would not necessarily expect FinCEN’s budget or staffing to grow at exactly the same pace as SARs. Nevertheless, staffing growth has been shockingly slow, dipping negative at times and only growing by three percent in eight years. Budget growth is stronger, with a 61% total increase. But the actual dollar amount is puny by U.S. government standards: about $185 million per year in 2022.8 For context, that is less than the yearly police budget of Mesa, Arizona.9

FinCEN is not alone. The UK’s FIU received approximately 860,000 SARs from 2022-2023, representing a 143% increased over a 10-year period.10 And things get really interesting if we look at FIU-Netherlands. The Dutch do things a bit differently. Unlike most countries, where financial institutions submit SARs, Dutch companies submit Unusual Transaction Reports. These UTRs are based on two categories: (1) objective indicators and (2) subjective indicators. Objective indicators are outlined in national legislation and include things like:11

A transaction for an amount of € 10,000 or more, involving a cash exchange into another currency or from small to large denominations

For buyers and sellers of works of art: A transaction of €20,000 or more.

These objective indicators are more like pieces of data than reports of client-specific suspicions. The latter fits into the second category of indicators, where companies have subjective reason to believe that some transaction may be related to a criminal scheme.12 As the Netherlands FIU explains, both serve their role: “the subjective reports provide a lead in themselves, whereas the objective reports generally provide additional information.”13 And, like their U.S. and UK counterparts, FIU-Netherlands has seen a tremendous increase in reports:

There are some jaw-dropping increases here. By 2018, FIU-Netherlands was receiving 273% more UTRs than it was just three years earlier with zero corresponding increase in budget or staff. But things got really interesting the next year. Total UTRs increased from approximately 753k in 2018 to 2.4 million in 2019. It turns out this was driven by the introduction of one specific indicator:14

The majority of these transactions…were reported on the basis of one specific objective indicator, linked to the high-risk countries designated by the European Commission. Of the total number of reports of 2,462,973 unusual transactions, no fewer than 1,921,737 were reported to FIU-the Netherlands in 2019 on the basis of this indicator.

Upon review, the agency found that only 686 of these 1.9 million UTRs were actually related to suspicious activity. So the sensible decision was made to adjust the indicator. And, with the flip of this switch, we see a massive reduction the next year. The underlying upward trend, however, remains. By 2022, FIU-Netherlands received 838% more UTRs than it did in 2013. 838%! But unlike FinCEN, there was a stronger corresponding increase in budget (153%) and staff (65%).15

What we see, in aggregate, are tremendous global increases in SARs and equivalent notifications. For regulators, this poses a data dilemma. They know that much of this reporting is unhelpful; it is widely understood that companies overreport (“defensive” reporting) to cover their corporate derrières.16 But FIUs are hesitant to discourage submissions that may actually contain valuable leads.

Modern-day regulators are not the first to encounter this dilemma. To the contrary, the issues FIUs are encountering — and, as we will see, their creative solutions — have historical precedent. Specifically, they can be traced back in time to an unexpected place: the contested seas of Western Europe in World War I.

The Blockade of Europe

In 1916, Robert Cecil, later the 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood, was facing challenges on multiple fronts. It was, by some measures, the bloodiest year of World War I, with the Allied Powers engaged in relentless battle against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. Cecil had been appointed the UK’s first Minister of Blockade — what a title — responsible for cutting off the Central Powers from international trade as a means of economic coercion. The Blockade of Europe was unprecedented in its scope. Allied Powers blocked not just the export of munitions and other weaponry, but also foodstuffs, grain, and other items which could be used for both civilian and military purposes (what we now call dual-use goods).17

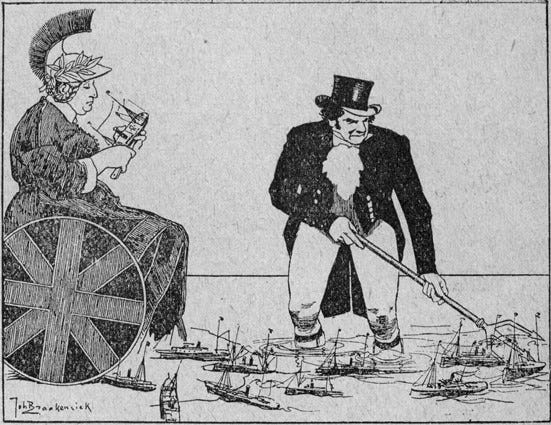

Economic blockades do not, however, enforce themselves. The UK had to dedicate much energy to controlling the North Sea, using its navy to intercept cargo ships bound for Germany with contraband. These ships were forced to stop in the UK for obligatory inspections, a process resented by neutral countries like the Netherlands (see the political cartoon below). The UK also disseminated “blacklists” of firms known to trade with the enemy.18

But physical goods were only one part of the story: these shipments also had to be financed. Ministry officials realized that the Central Powers were facilitating cross-border payments — likely disguised — to obtain funds and facilitate the secret shipment of contraband. How do you detect these payments? The solution, as Nicholas Mulder details in his deeply researched book, The Economic Weapon, would come not from the Ministry but from the City of London:19

The City banker E.F. Davies suspected that many trades through London involving neutral banks in fact hid profits from German firms overseas being repatriated to the Reich. Davies recommend that the ministry…[recruit] experienced traders from the City to spot suspicious transactions.

Cecil, seemingly convinced, allowed Davies to form a new Finance Section of the Ministry featuring bankers from Barclays and HSBC.20 They knew, however, that they possessed neither the resources nor staff to track every financial transaction themselves. As a solution, they proposed a reporting system, one that resembled (and in fact greatly exceeded in scope) those utilized by modern-day FIUs.

The Finance Section specifically required that UK-incorporated banks report data on weekly capital flows to and from neutral countries.21 These statistics empowered Davies and his colleagues to closely surveil international trade finance. As he summarized in a report:22

“Every consignment of goods crossing the seas which is financed in the United Kingdom under credits established with British banks can be followed by the Finance Section…including the names of the consignors and consignees, ports of shipment and destination, names of steamers, and dates of sailing, etc.”

It’s important to pause and fully appreciate what this means. The Blockade Ministry created, in essence, a state-controlled database through which they could directly surveil financial transactions and international trade. And they did it by requiring the private sector to continuously feed them with data. Not bad!

Modern-day FIUs do not possess quite the same power.23 They continue to rely on reports from the private sector; they are not able to directly monitor global financial transactions (let alone shipping data).24 But they are, in their own uncoordinated way, building reporting systems which resemble those of World War 1. Namely, they are transforming SARs from an ad-hoc report which must be manually reviewed to a source of searchable raw data.

From Report to Database

We normally think of SARs as a source of leads. This implies that every SAR must be closely analyzed by a human who will determine whether the lead warrants further investigation. But as the volume of SARs increases astronomically, the most advanced FIUs are transforming them into the building blocks of databases which can be queried and subjected to advanced surveillance techniques.

The FIU-Netherlands is a case in point. The “objective indicators” banks are required to submit are a form of data not unlike those which the UK Ministry of Blockade collected during World War I. As the FIU itself states: “[they] provide insight into money flows and can be valuable pieces of the puzzle in demonstrating a financial relationship or a specific pattern.”25

But it is not just objective indicators which can be transformed into data. Subjective indicators — closer to traditional SARs — are also included in the centralized database of FIU-Netherlands.26 Similarly, FinCEN and the UK FIU maintain databases in which specific SAR fields can be queried.27 If we think of SARs as data points rather than reports which must be manually reviewed, their pure volume may not be as much of a problem as it initially appears (and maybe not a problem at all).

But perhaps what is most interesting about these developments is the regulatory sleight-of-hand. There has long been a conflict between the state’s desire to detect financial crime and the public’s desire for privacy. SARs are, in essence, a compromise between these competing concerns. They represent an indirect form of monitoring, in which private financial information is only disclosed to FIUs if legitimate suspicions are present. But as the volume of SARs rises — and as regulators expand the range of SAR-worth material — they are transforming. Specifically, they are transforming from ad-hoc reports to growing databases of financial information which FIUs and other agencies can directly surveil. If Lord Cecil and E.F. Davies were still around, they would be raising their port glasses in approval.

Important exceptions include market abuse, where numerous regulators have obtained the independent capacity to directly surveil transactions. Another exception category is digital currencies, which operate via publicly-available blockchains which allow law enforcement to trace every transaction. Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman have also noted in their recent book, Underground Empire, that U.S. agencies have obtained the capacity to surveil inter-bank communications of transactions via the The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT).

Sometimes referred to as a Suspicious Transaction Report (STR).

As Matt Levine would write, not legal advice.

The budget numbers reflect appropriated and reimbursable resources for “BSA Administration and Analysis Resources and Measures.” Some years also include Treasury Executive Office for Asset For Forfeiture (TEOAF) Strategic Support. It does not, to my understanding, include things like “Recoveries” and “Unobligated Balances” from previous years and thus slightly underestimates total budget. For FY2022, for example, the category utilized for this figure is $185.6 million versus $211.9 million when you take into account Recoveries and Unobligated Balances. I chose to use the former figure because the latter appears to change substantially year-by-year without full recalculations of previous years’ statistics. Further, it is not entirely clear whether these numbers account for inflation. The reported total SARs in this congressional document is also inconsistent with some of the statistics reported by FinCEN on their website (something that Jim Richards also observed in a previous blog post). Thus, in sum, this data is all a bit messy and should be taken with a grain of salt.

See Footnote 6 for caveats.

Mesa, a town of half a million people, spends almost $200 million per year on policing, which may also say something about local police budgets…

Calculated based on yearly report data.

Translated from the Wwft Implementation Decree 2018, Appendix 1: List of Indicators.

The difference is well-explained in FIU-Netherlands’ 2021 Annual Report.

Ibid, p. 8.

FIU Netherlands 2019 Annual Report, p. 31.

Budget statistics have not been adjusted for inflation, as this may already be captured in the government’s yearly allocation (though I am no expert on this!).

The conceptualization of food as dual-use goods was highly controversial, and it has been estimated that the blockade of Europe directly contributed to the death of at least half a million civilians. Mary Elisabeth Cox explains the details of the classification process in her book, Hunger in War and Peace: Women and Children in Germany, 1914-1924.

Nicholas Mulder, The Economic Weapon, pp. 40-41.

Ibid.

Nicholas Mulder, The Economic Weapon, p. 50.

Quoted in Mulder, The Economic Weapon, p. 50.

But similar systems exist in other areas. See, for example, ACER’s surveillance of European energy trading.

If you live in a country where FIUs can do this, email me! I would love to know more.

FIU-Netherlands Annual Report 2021, p. 7.

FIU-Netherlands Annual Report 2022, p. 4.

Interesting, Miles. I’ve wondered for a while how many FIUs (or banks) that are relying on these models are building them, basically, inductively or deductively. Are they using known cases to build a dataset of ML patterns and then looking for those. Or are they building models of Not-AML and then looking for aberrations? Any idea?