The Designation Dilemma

Trump wants to designate drug cartels as terrorists. The economic impact, both for America and Mexico, could be disastrous.

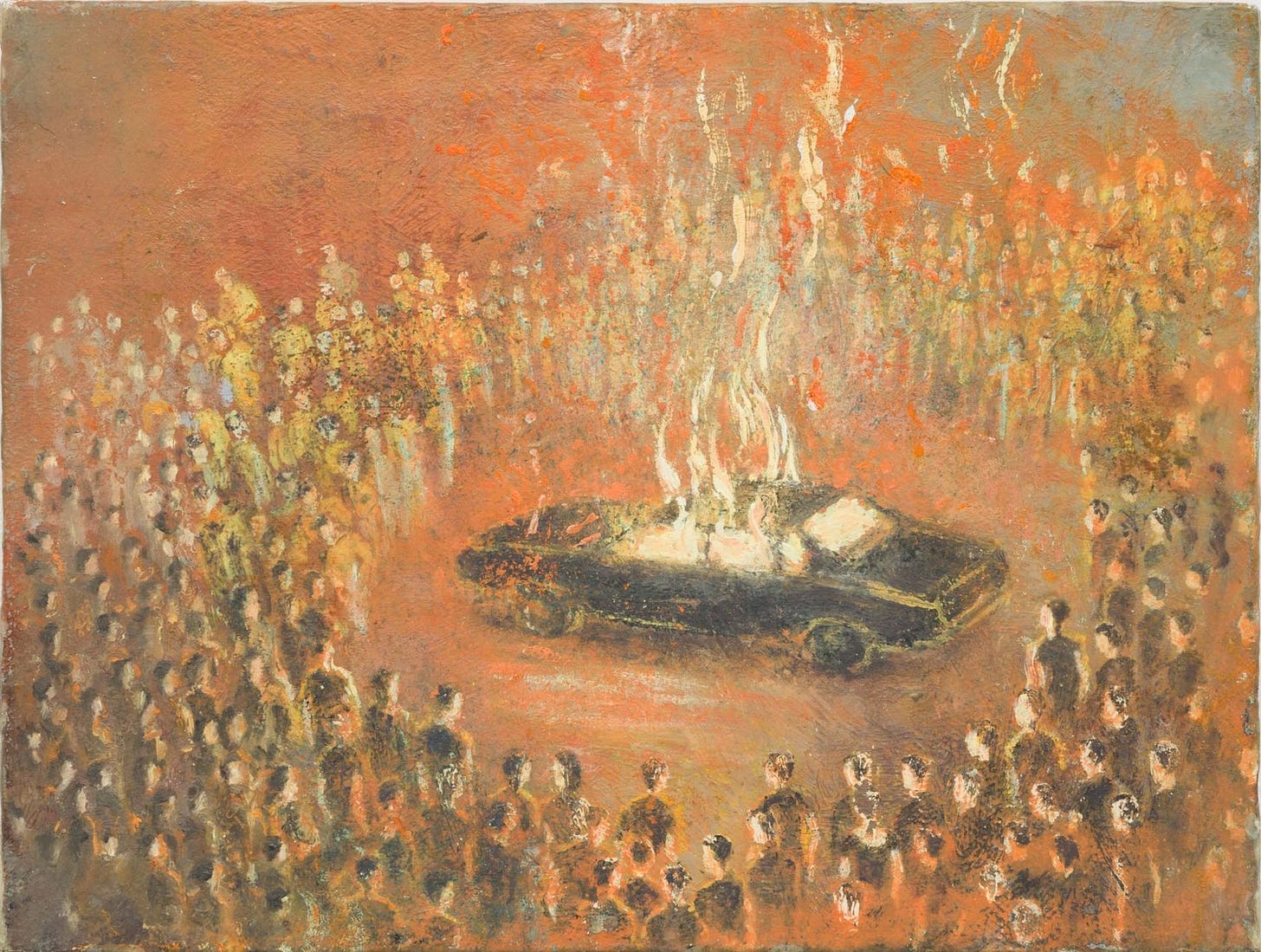

In Veracruz, a region of Mexico which curves around the glittering waters of the Gulf, there are 12 outdoor brick ovens. These ovens were created to cook zacahuil, a corn dish similar to the Mexican tamale. But throughout the 2010s, they were used for a very different purpose: incinerating human beings. Search teams — led primarily by volunteers seeking lost loved ones — have discovered thousands of gallons of organic material among the ashes.1 Accompanying these remains are the horrific traces of extermination. Machetes. Ragged blindfolds. Charred handprints and the scribbled names of victims on pink-colored walls.

Responsible for operating these “kitchens” was Los Zetas, a Mexican drug cartel infamous for their brutality.2 Bodies were burned in ovens or, in some cases, only after having first been dissolved in large barrels of acid.3 There are hundreds of victims. But this accounts for only a small fraction of the 115,000 Mexicans reported missing as of August 2024.4 And these extermination sites are only one example of the atrocities committed by the cartels.5 In October, the newly elected Mayor of a major city was beheaded.6 Tortured bodies, meanwhile, are periodically hung atop federal highways to instill maximum fear.7

Thus it was not entirely surprising when Trump, on his first day of office, issued an Executive Order to designate Mexican drug cartels (among other groups) as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs).8 At first glance, this appears uncontroversial. Cartels employ mechanisms of violence very similar to those used by Hamas, ISIL, and other widely-recognized terrorist groups.9 And previous presidents, from Bush to Obama, have debated making the same designation.10

Yet every prior administration, including Trump’s, has resisted. One reason is political. The FTO designation allows the U.S. to undertake military action abroad — something Mexico may view as a violation of its sovereignty.11 And there has long been legal wrangling over definitions. Some argue cartels can’t be labeled as terrorists because they lack clear political objectives.12 Others question whether they truly pose a threat to Americans — an essential condition of FTO designation.13 Regardless, Trump is forging ahead. And his new administration has made it abundantly clear that it has little concern for mere legal constraints.

But there is another type of constraint — one Trump does care about — that may catch their attention: designating cartels is bad for business. The FTO label is first and foremost a financial weapon. Its primary objective is to cut terrorists off from the global financial system. And it achieves this by imposing strict obligations on private companies to avoid any exposure to FTOs or their associates. These rules reverberate throughout financial networks, causing chain-reaction patterns of de-risking which slowly isolate targets from the legitimate economy.

Normally, imposing the FTO designation on terrorist groups doesn’t pose any real economic risks. American markets aren’t particularly exposed to the Tamil Tigers or the New Irish Republic Army.14 But the cartels are different. The sad reality is that they are deeply embedded into the ‘legitimate’ Mexican-American economy. Limes, avocados, plastics, minerals, raspberries, tourism…the cartels are a pervasive presence on both sides of the border.15 Asking the private sector to de-risk from these groups, then, is easier said than done. Can America — and Trump — really stomach the costs? Or are Mexican drug cartels simply too big to fail?

Economic Entanglements

This is not the first time concerns have been raised about the economic consequences of FTO designation. In the early 2010s, U.S. policymakers debated applying the label to Boko Haram, an Islamic extremist group in Nigeria.16 Among other objections, Nigerian officials cautioned that labelling Boko Haram as terrorists would disrupt the flow of humanitarian aid.17 And, indeed, the FTO label can make life very difficult for such programs. Banks, incentivized to de-risk, may conclude that serving humanitarian organizations is no longer worth the compliance headaches.

The cartels, however, are a whole different beast. For obvious reasons, it is difficult to measure the full extent of their involvement in Mexican-American trade. But there are indicators. The American Chamber of Commerce in Mexico, for instance, runs a yearly survey of business leaders on security concerns. In 2024, 12% of respondents stated that “organized crime has taken partial control of the sales, distribution and/or pricing of their goods.”18 For 1%, organized crime had taken “total control.”19 You might be thinking: “well, only 13%.” But think about what this means. A substantial proportion of Mexican executives are admitting — in a survey — that cartels exercise managerial control over their own businesses. Not good!

And there is reason to suspect these numbers underestimate the cartels’ presence in the legitimate economy. One recent study estimates that the full population of cartel members in 2022 was between 160,000 and 185,000.20 That would make the cartels Mexico’s fifth largest employer. The Treasury Department will not, of course, designate hundreds of thousands of people as terrorists. But companies around the world will now have to evaluate, on a counterparty-by-counterparty basis, if it is safe to deal with large portions of the Mexican economy.

Some readers may be thinking: wait, isn’t this already a thing? Companies have long been obligated to perform Know-your-customer checks on clients. And the U.S. has imposed sanctions on narco-traffickers ever since the passage of the Kingpin Act in 1999.21 This includes individuals linked to Los Zetas, the Gulf Cartel, and, of course, the granddaddy of them all: the Sinaloa Cartel.22

But the FTO designation is different. It unleashes the most intensive form of economic sanction, one which carries extreme penalties for non-compliance and complex new questions about liability. Questions which may lead many companies to conclude that, when it comes to Mexico, the sphere of acceptable risk is collapsing.

Risky Business

The problem, for companies, is not just about due diligence. It is also the tremendous operational risks posed by FTO designation. One example is extortion. If a cartel forces you to pay ‘protection fees’ or charges for permission to operate in their territory (also known as Derecho de Piso), this could now be interpreted as “materially supporting” a terrorist organization.23 This is very illegal. So illegal, in fact, that it can lead to life imprisonment if it leads to the death of any person.24

But how likely is it that a business is extorted? Well, according to the Chamber of Commerce survey, more than 80% of business executives view extortion as a high or medium security risk in Mexico, with 41% — read that again: 41%! —- having been digitally extorted in the past year.25 Another survey, operated by Mexico’s statistical agency, found that extortion is the most common crime suffered by businesses (25.5% of total).26 Separate research by the National Citizen Observatory shows a correspondingly bleak trend:

These numbers paint a clear — and grim — picture. Namely: if you do business in Mexico, there is a very high risk of being extorted by drug cartels. This is bad enough for companies. But at least they haven’t had to also worry about the legal risks of being victimized. Paying ransom, you see, is generally not considered illegal under U.S. law.27 With one important exception: paying ransom to terrorists or other persons subject to economic sanctions. As the U.S. Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) warned in 2021:

[OFAC] is issuing this updated advisory to highlight the sanctions risks associated with ransomware payments…ransomware payments made to sanctioned persons could be used to fund activities adverse to the national security and foreign policy objectives of the United States…Facilitating ransomware payments on behalf of a victim may violate OFAC regulations...28

Ransomware is a type of malicious software program often used to digitally extort organizations. And what OFAC implies here is that paying that ransom may be illegal if the perpetrator is subject to economic sanctions. But it gets worse. OFAC emphasizes that it can punish such violations based on the legal standard of strict liability. What this implies is that paying extortion could be considered illegal “even if such person did not know or have reason to know that it was engaging in a transaction that was prohibited under sanctions laws…”29

What does this all mean in practice? Imagine, for a moment, that you run a business which exports raspberries from Mexico to Arizona. For years, a drug cartel has forced you to pay fees for driving trucks through its territory. This is bad. But if you don’t pay, they may kill your employees. So you pay. But according to Trump, these aren’t just criminals anymore — they’re terrorists. So paying them now might be a violation of sanctions law, even if you aren’t aware they are an FTO. The consequences, both for yourself and your company, could be disastrous. You could potentially spend the rest of your life in prison. What do you do?

The Risk Multiplier Effect

This problem isn’t constrained to companies operating in Mexico. It also extends to their banks, payment service providers, and insurers. These institutions are prohibited from facilitating payments which may violate sanctions law — like extortion payments to terrorists. But what do you do if, say, 41% of your clients in Mexico were extorted in the last year? How can you possibly mitigate the risk?

One option is to ask more of your clients. Providers of ransomware insurance, for example, increasingly require Mexican clients to purchase expensive cybersecurity solutions to qualify for coverage.30 Perhaps you could also ask raspberry importers to have armored convoys to protect their trucks rather than paying cartels. But all of this just adds costs throughout the supply chain. And, for many clients, it simply won’t be realistic. The simpler alternative is to step away. What we could see, in other words, are layers and layers of financial service providers slowly concluding that business in Mexico is no longer worth the risks.

This can be thought of as a multiplier effect. Economic systems are network structures connected through various forms of financial intermediation. When companies on the ground face some new risk, that risk permeates throughout the network toward their bank, their insurer’s bank, their insurer’s bank’s bank, etc. There is no theoretical limit to the layers of indirect exposure when it comes to terrorist financing. Thus, when you label a major economic player like cartels as terrorists, you poison — for better or worse — the well from which the whole system drinks.

But de-risking from Mexico at scale simply isn’t feasible. Mexico is America’s second-largest trading partner.31 And as the above map demonstrates, numerous U.S. states are heavily dependent on Mexican imports. Both countries are linked by hundreds of billions of dollars of investment and trade, not to mention more than $63 billion in cross-border remittance payments.32

What the U.S. faces, in other words, is a designation dilemma. It wants to designate Mexican drug cartels as terrorists — with good reason. But the FTO designation, if applied widely and fully implemented to its logical conclusion, could quite literally destroy the American economy. It creates a new level of legal risk, one featuring extreme penalties and standards of liability, that self-perpetuates throughout the financial system. And when that risk pertains to groups who play a major role in international trade, economic exchange is frozen.

Perhaps the Trump administration proceeds anyway. Perhaps, despite the risks, it will move fast and break things. But what is more likely, in my view, is that they mitigate the effects. Perhaps the scope of designations will be limited. And it is plausible — though far from guaranteed — that the U.S. could update their enforcement guidance to provide bewildered companies more relief from the legal risks. Regardless, they will have to do something. Because designating terrorists is easier said than done when legitimate and illegitimate worlds collide.

For a remarkable ethnographic account of these horrors, read Melenotte, S. (2025). La Gallera: Los Zetas’ extermination camp in northern Veracruz, Mexico. Violence: An International Journal, 26330024241307243.

Ibid.

Ibid. See also Eoin Wilson, ‘Worse than any horror film’: Inside a Los Zetas cartel ‘kitchen’.

See also George W. Grayson, The evolution of Los Zetas in Mexico and Central America: Sadism as an instrument of cartel warfare.

Mary Beth Sheridan, Trump designated drug cartels as terrorists. Here’s what that means.

Paul Rexton Kan, El Chapo Bin Laden? Why Drug Cartels are not Terrorist Organisations.

Nathaniel Parish Flannery, Are U.S. Avocado Buyers Financing The Cartel Conflict In Mexico?; Tracy Wilkinson and Ken Ellingwood, Cartels use legitimate trade to launder money, U.S., Mexico say; Maria Abi-Habib and Simon Romero, How Labeling Cartels ‘Terrorists’ Could Hurt the U.S. Economy.

Ibid.

Rafael Prieto-Curiel et al. ,Reducing cartel recruitment is the only way to lower violence in Mexico.Science381,1312-1316(2023).DOI:10.1126/science.adh2888

Treasury, Narcotics Sanctions Program.

Asaf Lubin, The Law and Politics of Ransomware.

Ibid. See also Jones Day’s OFAC Guidance on Ransomware Payments Highlights Sanctions Violations Risk.