The (Dis)assembly of Information

Chinese crime syndicates are operating underground banks to launder the proceeds of fentanyl sales. But their practices, and the risks they pose, are far from new.

One way of thinking about finance is to imagine it as an endless web of information assembly lines. Every transaction starts as a signal: some person wants to buy some thing. This is the raw material of demand. That material must, in turn, eventually make its way to whomever is in a position to supply. Sometimes this is easy. When you buy mangos at a farmers market, for example, you have direct communication with the supplier, handing over cash with one hand while receiving mangos with the other. But such direct interaction is rare. For most transactions, buyer demand must first travel along informational conveyor belts, where intermediaries shape, mold, and redirect that raw material before it reaches suppliers.

Take residential real estate. If a couple wants to purchase a beachfront bungalow in Santa Barbara, they probably aren’t going to just show up at the front door with a duffle-bag full of cash. That would be weird. Rather, they are much more likely to express their demand through a realtor. This information then makes its way down the assembly line, where it passes through a series of intermediaries: the seller’s realtor, title company, mortgage advisor, attorney, and, finally, the bank.

But buyers and sellers are not the only ones interested in this process. There is also the inquisitive eye of the state. Every stage of the information assembly line contains clues — about unpaid taxes, money laundering, terrorist financing, and all sorts of other shenanigans. The state would love to patrol every assembly line looking for these clues, like a mustached inspector peering over the shoulder of nervous factory workers.1 But this is expensive. And many of us would prefer that our information is assembled by intermediaries in private.

The state’s solution to this problem has been to outsource surveillance. It requires that certain intermediaries on the information assembly line look for signs of suspicion and report those suspicions to regulators. These are what is referred to as Anti-Money Laundering, or AML, obligations. At the risk of abusing the analogy, intermediaries with AML obligations are like factory produce inspectors. They spend all day staring at fruit as it travels across the conveyor belt, sorting out the rotten apples and tossing them into separate bins.

But what if, somewhere along the production line, the informational conveyor belt just…disappears? The Financial Times has reported that Chinese crime syndicates are capable of performing such sorcery.2 These syndicates, the FT writes, are using a “new” network to launder the proceeds of fentanyl sales, one that “…minimizes the movement of funds across borders.” The money simply disappears in one place and reappears in another, as if governed by quantum physics. But this is not magic. Nor is it new. It is instead an alternative conveyor belt of information, one that has operated outside the confines of the state for over a thousand years. And it goes by a simple yet ominous name: underground banking.

Six Feet Under

Imagine, for a moment, that you are a textile merchant somewhere along the 6,000 kilometer stretch of the ancient Silk Road. Every business has risks. But your risks are a bit more extreme. Large stretches of your trade routes are located in harsh desert climates where water is sparse. Nor is there any guarantee of security. Nomadic raiders could strike your caravans at any moment. And, even if you survive the trip, you could arrive to your destination only to find that it has been sacked by Attila the Hun (or, later, the roaming armies of Genghis Khan).3

The last thing you want to do, in such a dangerous environment, is carry cash on you. Credit cards would be a great alternative. “No!” you might explain to Chase customer service after having your card stolen by Hun raiders, “I definitely did not order horse archers.” But it’s about 600 - 1,900 years too early for that. In this pre-electricity era, you need an alternative system. Specifically, one that allows you to manage your payments, settle outstanding balances, and avoid the perils of carrying money across the Persian desert. Enter Hawala.

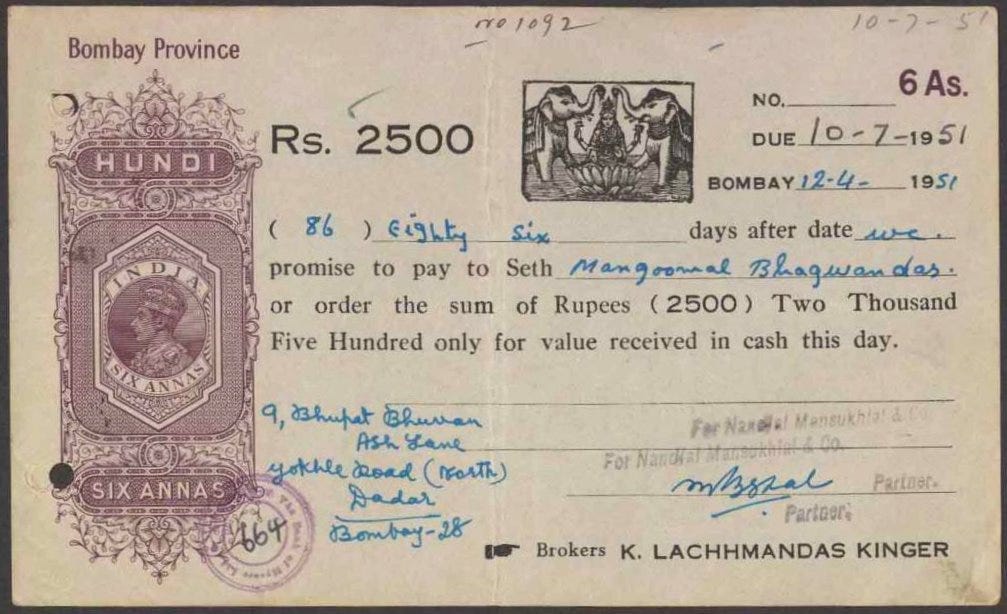

Hawala is an Arabic term roughly meaning “to change” or “to transfer.”4 It refers to a system in which networks of brokers (hawaladars) facilitate the movement of value from one geographic location to another.5 Nobody really knows when Hawala was first used. But there is evidence from the 6th century that Muhammed, the founder of Islam, was familiar with at least some version.6 Similar systems, with equally ancient roots, have existed in India (Hundi), Thailand (phoe kuan), and China, whose term Fei-Chien translates to flying money.7 And they have collectively come to be referred to as different varieties of “underground banking.”

Here’s how a Hawala transaction might have worked on the Silk Road.8 Say you are a merchant in Iran who wants to import Aleppo pepper from Syria. Rather than drag heavy coins across the desert, you provide the necessary money (in whatever form was used at the time) to your local broker.9 In return, the broker would issue what was, in effect, a bill of exchange — a written order to pay an equivalent amount of money to the supplier at a later date. Once you arrive to Aleppo, you present that document to a Syrian broker, who honors the bill of exchange by issuing the money to the supplier in local currency.10 Each broker charges a commission for their services and settles their balances through repeated business.

With this simple maneuver, currency has been exchanged across borders.11 But rather than physically moving money from one place to the next, the brokers have received and distributed local currency from their respective pots.12 The only true transfer is one of information. Specifically, the buyer’s broker communicates that their client has deposited some amount of money in one pot (in Iran) and thus can be credited an equivalent total from the second pot (in Syria). Trust is essential here. So too is the reputation of brokers to honor one another’s bills of exchange.

Trust is also essential to contemporary Hawala systems. But today’s networks are more focused on facilitating cross-border payments and currency conversions rather than international trade. Remittances are one important example. If a worker in Belgium wants to send money to their family in Pakistan, they can do so through their local Hawala broker. But unlike their ancient predecessors, there is no need for these brokers to issue a bill of exchange.13 They can simply pick up the phone or text their foreign counterparts that the money has been deposited.

But how can the worker be sure that the person picking up the money is actually their family member? One common solution: secret codes.14 Hawala brokers will often require each party to express these pre-agreed codes, which could be as simple as reciting the same verse from the Quran.15 Another option, observed in a Chinese context, is to present a sugar cube with a specially imprinted symbol — and swallow it once the transaction is complete.16

You might be thinking that, aside from the secret sugar cubes, this all sounds pretty familiar. And you would be correct. Hawala is, in essence, the earliest known form of trade finance. It is also a predecessor to “modern” payment institutions and foreign exchange providers. As one such institution, Wise, writes:

Wise takes what’s good about Hawala and marries it to strong and reliable banking regulations that keep your money safe. Like Hawala, Wise uses [a] peer-to-peer system to send money abroad, but with bank accounts. However, unlike Hawala, Wise is not informal, nor outside the banking system. In fact, quite the opposite. In order to operate, Wise is licensed by local financial regulatory bodies…17

One striking aspect of this paragraph is the distinction Wise makes between ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ economic systems. Wise implies that Hawala is informal because it is not regulated by the state. This is the same logic often applied to characterize such networks as “underground” banking systems. There is a historical irony here. Hawala, Hundi, and similar networks operated for hundreds of years before ‘states’ were a thing. And in some situations, such as the British Raj, sovereigns endorsed their use as indigenous forms of payment.18 Thus ‘formality’ is probably better thought of as a spectrum here, one which depends on both the state’s desire to regulate and the market’s desire to be regulated.

Nevertheless, Wise is correct that hawaladars are largely unregulated.19 In fact, they are outlawed in many countries, something Wise — a competing service — is keen to emphasize.20 And the reason is simple: Hawaladars often maintain fewer records of the transactions they facilitate for their clients.21 They disrupt, in other words, the informational assembly lines of the ‘formal’ financial system, undermining the capacity of the state or its intermediaries to perform surveillance. And this is music to the ears of a particular clientele. Namely: human traffickers, terrorists, and other actors with nefarious motives to move their money in the dark.

Information Disassembled

If you want to send money from Arizona to the Philippines, you can do so through Western Union. But it will require that you participate in the information assembly line of the state-controlled financial system. The first step is to open a bank account, which will require that you provide, at minimum, verifiable identification, proof of address, and information on how you obtained your money. Western Union will then facilitate the transfer. But if your account is held at another bank, they will also ask for ID and may perform their own due diligence checks. Further, it has been reported that Western Union is sharing transactional data with U.S. law enforcement.22 Thus, by the time your click send, your information has been dutifully assembled and is now subject to no less than three layers of surveillance.

Hawaladars operate very differently. Contrary to the popular narrative that these are “paperless” systems, these brokers do maintain records.23 It would be very difficult to operate without some tracking of inflows and outflows. But they generally don’t care about where the money came from.24 Nor are they likely to ask for a passport or perform any type of transaction monitoring.25 Even if they wanted to — which they don’t — they can only see the transfers they facilitate, and thus, as one study notes, “the records are as distributed as the system itself.”26

These minimal record-keeping practices are driven in part by competition. Hawaladars compete both with the regulated financial sector and each other. If one broker starts asking for all sorts of documentation, customers are likely to be spooked and seek out an alternative.27 Assembling information is also very expensive. Banks spend ungodly amounts on maintaining and surveilling customer data. Free from these obligations, Hawaladars can charge a much lower commission than regulated firms and often settle transfers at faster speed.28

But those commissions may rise when Hawaladars and other informal money brokers serve more dubious clientele. One study finds, for example, that certain Hawaladars are willing to facilitate the movement of criminal funds — albeit at a higher commission rate of 15-20%.29 And while the great majority of transactions are likely innocent remittances, there have been numerous cases of Hawala brokers being used to facilitate terrorist financing. This includes Osama bin Laden, who used Hawala brokers to move money for Al Qaeda prior to 9/11.30

Criminals and terrorist groups are attracted to Hawala because of its minimal record-keeping requirements. It allows them to escape the information assembly lines of the state-controlled financial system. Phrased differently, it facilitates alternative conveyor belts of information which can’t be easily surveilled. And this is precisely why Mexican drug cartels and other criminal organizations are increasingly using the services of Chinese underground banks.

The Underground Silk Road

In January 2021, Peiji Tong — also known as Dr. P — crossed the border from Mexico to the U.S. (picture below). According to the Department of Justice, Dr. P was not on vacation. Rather, he was meeting with members of the Sinaloa drug cartel to discuss how he would launder their money.31 The cartel was in desperate need. Their profits have exploded from selling fentanyl, a horribly addictive opioid 10,000 times stronger than morphine (hat tip to the Sackler family).32 And, as is so often the case, selling the drugs is much easier than laundering the profits.

Luckily for the Sinaloa cartel, the doctor was in. Tong and his associates helped the cartel move their money across borders through Chinese networks of informal money brokers. And they did so by capitalizing on growing demand amongst (particularly wealthy) Chinese families to move their money abroad. Many of these families are fearful that the Communist Party could, at a moment’s notice, seize their wealth for political reasons.33 The Chinese government has set a $50,000 cap on outgoing transfers to limit this ‘capital flight,’ providing its citizens with incentives to make their money fly instead through informal brokers.

Here’s how it worked. Chinese nationals would provide renminbi to informal brokers located in China. The brokers would subsequently use encrypted messaging apps like WeChat to communicate to their counterparts in the U.S. that they may release an equivalent total in dollars. The Chinese customers could then arrange for that money to be picked up by someone in America. But what many of these customers may not have known is that those dollars were the proceeds of fentanyl sales. Dr. P and his associates had injected the cartel’s money into the underground banks so that they could be sold to the Chinese. It’s a simple trade. The Chinese satisfy their demand for dollars. The cartel, in return, is able to transport its illicit profits to China in the form of renminbi. Classic Hawala — with a criminal twist.

But what recent reporting has struggled to explain is that this was not the end of the money laundering process. Hawala moves money — it doesn’t clean it. Cartels still need to find a way to inject that cash into the financial system to make it appear as if it was derived from legitimate sources. Per the indictment, the cartel performed this step through one final sleight-of-hand.34 Once their dollars were transformed into renminbi, they would arrange for Chinese businesses to use that renminbi to purchase products from Mexican businesses controlled by the cartel. This, in turn, generated local profits in pesos which appeared legitimate. Thus, in sum, cartel profits travelled through an underground Silk Road, first from the U.S. to China and then from China to Mexico, where it emerged, clean as a whistle.

Here we see both the benefits and limitations of Hawala as a mechanism for financial crime. Like their ancient predecessors, Chinese brokers can move money from one place to another without a trace, sidestepping the informational assembly line of the state-controlled financial system. But additional steps are needed to actually launder the cash. And these steps often involve re-entering the assembly line by interacting with regulated intermediaries. The Chinese businesses buying Mexican products for the cartel, for instance, would have done so through banks with standard obligations to perform AML checks. Thus Hawala can obscure the movement of cash but cannot protect that cash once it enters the ‘formal’ economy.

And there is another caveat: a big one. Chinese underground banks move money through alternative conveyor belts of information which rely on the use of ‘encrypted’ WeChat texts. But are these really so secure? It is commonly understood that the Chinese state surveils WeChat and other messaging services.35 This has led some to speculate that certain Chinese government officials must be participating in these underground networks.36 Perhaps we will never know.

What we can say for certain is that the use of app-based communication is a deep security vulnerability for underground banking. These networks are attractive to drug cartels and other bad actors because they disrupt transactional audit trails. Phrased differently: they disassemble information. But communication can undermine these benefits by creating another type of paper trail, one that reassembles how cash moves from one pot to another. Criminals should take note. And so too should any public officials that may be assisting them. To paraphrase the great Lester Freeman, if you follow the cash, you’ll find the money brokers. But if you start to follow the texts, you don’t know where it might take you.

Though there are also situations where the state may benefit from not knowing about a problem to avoid the subsequent responsibility to fix that problem. Jack Seddon and I talk about this in our recent article, Into the ether or the state? Legibility theory and the cryptocurrency markets.

Largely replicating previous reporting in 2022 by ProPublica.

See, e.g., Peter Frankopan, Silk Roads; Lisa Blaydes and Christopher Paik, Trade and Political Fragmentation on the Silk Roads: The Economic Effects of Historical Exchange between China and the Muslim East.

Saeed Al-Hamiz, Hawala: A U.A.E. Perspective.

See, e.g., Joseph Wheatley, Ancient Banking, Modern Crimes: How Hawala Secretly Transfers the Finances of Criminals and Thwarts Existing Laws.

Edwina A. Thompson, Misplaced blame: Islam, terrorism and the origins of Hawala.

Matthias Schramm and Markus Taube, Evolution and institutional foundation of the hawala financial system; Harjit Sandhu, Terrorism-Criminal Nexus: Non-banking Conduits.

Take this with a grain of salt, as these practices varied tremendously across regions and throughout the thousand-year history of the Silk Road.

In some periods and regions this may have been an agent of the sovereign rather than a fully private operation. For great details on these different systems, see Dan Du, "Flying Cash:" Credit Instruments on the Silk Roads.

The references to “Iranian” and “Syrian” currencies are used for the purpose of the example. What exactly was used for currency in each region varied throughout history and may, at times, have been the same (thus negating the foreign exchange component of the transaction).

Assuming there was actually a recognized “border” between these two regions at this time.

This is sometimes referred to as a “two-pot system.” See Matthias Schramm and Markus Taube, Evolution and institutional foundation of the hawala financial system.

Though they still might in some scenarios. See Maryam Razavy and Kevin D. Haggerty, Hawala Under Scrutiny: Documentation, Surveillance and Trust.

Maryam Razavy and Kevin D. Haggerty, Hawala Under Scrutiny: Documentation, Surveillance and Trust.

Ibid.

See Jyoti Trehan, Underground and Parallel Banking Systems.

Marina Martin, Between informality and formality: Hundi/Hawala in India.

“While Hawala may sound like a dream come true to some, there’s a caveat. A big one. Hawala is illegal…Hawala has become infamous as an easy way to fund dangerous and suspicious activities” so proclaims Wise.

Dustin Volz and Byron Tau, Little-Known Surveillance Program Captures Money Transfers Between U.S. and More Than 20 Countries.

Maryam Razavy and Kevin D. Haggerty, Hawala Under Scrutiny: Documentation, Surveillance and Trust; Roger Ballard, A Background Report on the Operation of Informal Value Transfer Systems (Hawala).

But there are exceptions! One fascinating study of Hawala dealers in Afghanistan were found to have implemented rudimentary KYC procedures, including photocopies of customer passports.

Ibid, 32. It’s worth noting that the same problem exists in the regulated financial system.

Ibid. It’s worth noting that the same dynamic very much applies in the regulated financial system, inducing some firms to cut corners to remain client-friendly.

ICCT, Al Qaeda’s Means and Methods to Raise, Move, and Use Money. See also the U.S. Senate Hearing on HAWALA AND UNDERGROUND TERRORIST FINANCING MECHANISMS.

Per the indictment.

See Patrick Radden Keefe, Empire of Pain.

Highlighted by the FT and ProPublica in their reporting.

The indictment is a little hazy on the details: “The funds that are transferred in China to the broker are then used to pay for goods purchased by businesses and organizations in Mexico, Colombia, or elsewhere such as consumer goods or items needed to aid the drug trafficking organization to manufacture illegal drugs, for example, precursor chemicals, including fentanyl. Once the goods are sold, generating local currency (for example, Mexican pesos), the proceeds are returned to the drug trafficking organization that provided the dollars in the United States. In this way, the funds from China facilitate the laundering of drug trafficking proceeds from the United States to the source country, while at the same time providing United States dollars to the individual from China who initiated the transaction.”

See, e.g., Stephen McDonell, China social media: WeChat and the Surveillance State.

See Sebastian Rotella and Kirsten Berg, How a Chinese American Gangster Transformed Money Laundering for Drug Cartels.

Really interesting article on a contemporary problem but with a deeply engaging history. It would appear that crypto currencies also dissemble information and can potentially allow for similar sleights of hand by ensuring the anonymity of user. My understanding of crypto is rather limited, but I was wondering if you see a similar set of concerns.

The broader point regarding the benefits/dangers of technology is also really interesting. To some degree it seems many technologies or processes can be exploited even if designed with benign purpose.