Why ASML Matters

ASML is threatening to leave the Netherlands. For the Dutch, this is not just an economic problem: it is a matter of national security.

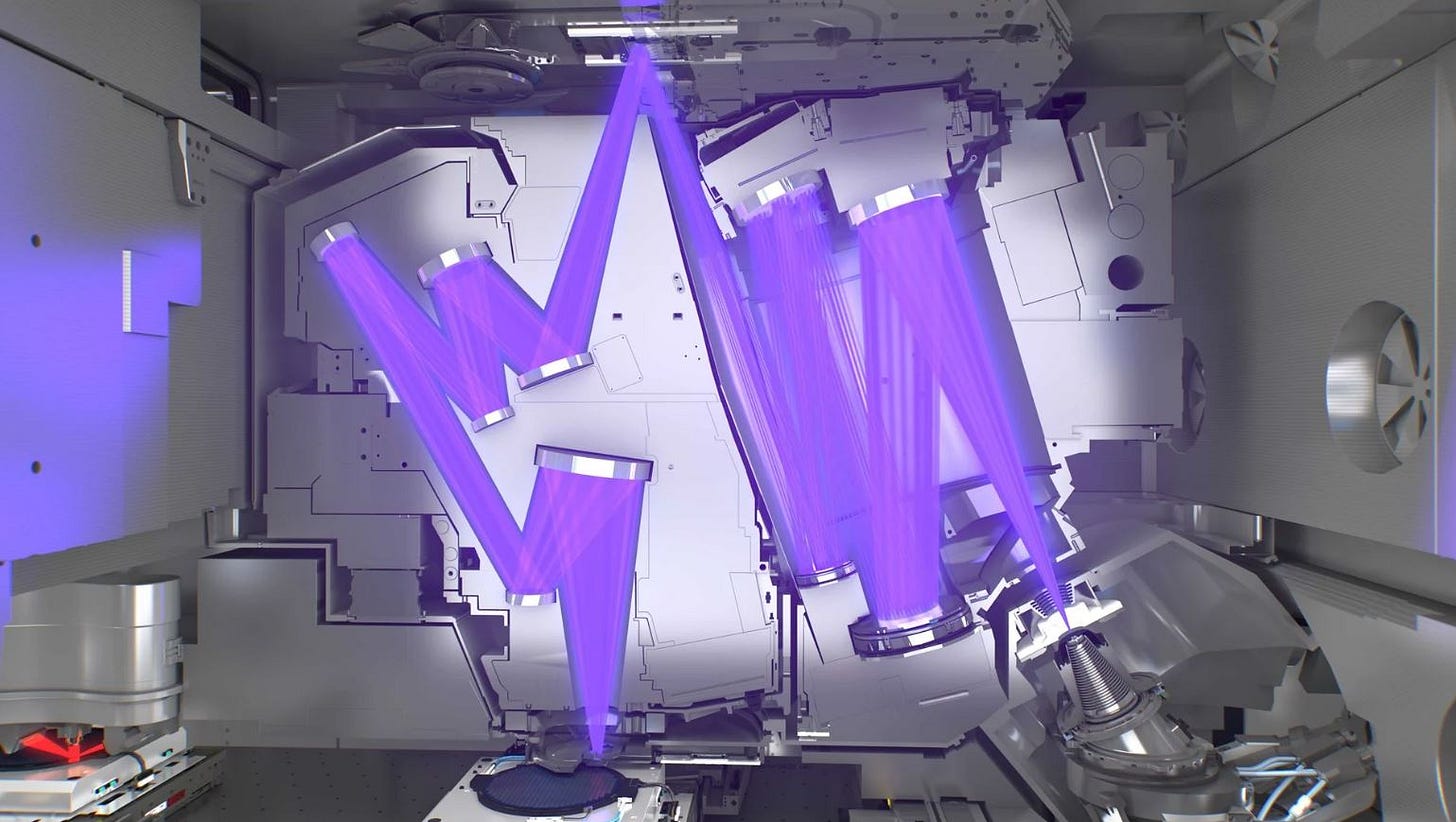

We all love that feeling when a special package arrives in the mail. For some it might be a new sweater. For others, it’s an electric-powered mosquito trap that you buy online despite that they never work.1 But in January, tech giant Intel received a truly remarkable delivery: the world’s first “TWINSCAN EXE:5200.”2 This system contains approximately 100,000 separate parts, whose delivery requires three cargo plans, 20 trucks, and 40 freight containers.3 But this is only the first step. Once Intel receives these parts, it takes 250 engineers six months to reconstruct the system onsite, which eventually weighs the equivalent of 150,000 kilograms, or about 22 fully grown African elephants.4 The price: $380 million.

Intel was willing to spend such great sums because the TWINSCAN EXE:5200 is the world’s most advanced extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography system. EUV lithography is the process of employing rays of light to print cutting edge microchips.5 Each chip contains billions of individual transistors which determine their speed, efficiency, and capabilities. The TWINSCAN EXE:5200 prints these transistors by shooting rays of light through mirrors. But these are not just any mirrors. They have been engineered as the smoothest surfaces on Earth to ensure that each beam of light travels at incredible levels of accuracy. As Chris Miller summarizes in his fabulous book, Chip War, this system of EUV lithography is so accurate that it could be employed to hit a golf ball on the Moon with a laser.6

And there is only one company on the planet that creates these systems: Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography. ASML, as it is more widely known, is a Dutch company headquartered just outside Eindhoven. Through decades of research and many billions of Euros in investment, ASML single-handedly developed the practical application of EUV lithography.7 There is no market for this product. It is a singular scientific achievement through which ASML has obtained a complete monopoly on the means of producing the world’s most advanced microchips. Without ASML’s systems, companies like Intel cannot manufacture the chips used in the world’s most sophisticated technological devices. This includes self-guided missiles, drones, and other military applications that will significantly impact who has the “edge” in our current era of great power competition.

But in March, the Dutch government received deeply unsettling news: ASML is threatening to leave the Netherlands.8 ASML has expressed concerns that recent proposals to curb immigration, including limiting foreign students and ending tax breaks for highly skilled immigrants, will make it harder to attract talent. CEO Peter Wennink bluntly stated in January: “The consequences of limiting labor migration are large, we need those people to innovate. If we can't get those people here, we will go somewhere where we can grow.”9

Many outlets have cited this as the latest example of the Netherlands’ deteriorating corporate environment.10 And, indeed, since Mark Rutte became Prime Minister in 2010, Unilever and Royal Dutch Shell — two Dutch titans — moved their headquarters to London.11 But ASML is different. This is not just another big multinational. This is a company with a monopoly on the means of future warfare. Not since the Dutch East India Company has a corporate actor been so important to the geopolitical future of the Netherlands. Keeping ASML’s major EUV lithography operations is not, in other words, an economic question. It is a matter of national security.

Choke Points

ASML personifies the political power of economic networks. As the sole supplier of EUV lithography systems, its sales determine who is capable of mass producing the world’s most advanced microchips. The list is not long: Intel, Samsung, and Taiwan’s TSMC account for about 80% of EUV sales.12 ASML is, in other words, a key “hub” in the global supply chain network of microchip production. And as Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman have theorized, states can weaponize such hubs to exert costs on their adversaries.13 One method is the “chokepoint” effect:

Because hubs offer extraordinary efficiency benefits, and because it is extremely difficult to circumvent them, states that can control hubs have considerable coercive power, and states or other actors that are denied access to hubs can suffer substantial consequences.14

We have already seen this tactic used on ASML. In 2018, the Netherlands provided ASML with a license to export its most advanced lithography machine (at the time) to a Chinese buyer.15 The U.S. immediately sought to block the sale and, following intense lobbying by the Trump administration, the Dutch government refused a renewal of the license and the machine was never shipped.16

This does not mean ASML is precluded from dealing with China. To the contrary, the company has an office in the country and Chinese buyers accounted for more than 23% of global net sales in FY2023.17 But for its most advanced products, ASML must procure a license from the Dutch government. As the company warns investors in their latest annual report:

We are required under Dutch regulations and other applicable legislation to obtain licenses for the export of certain technologies. In some cases, such licenses have not been granted or renewed. For example, at the end of 2023, the Dutch government partially revoked a license for shipment of NXT:2050i and NXT:2100i systems, impacting a small number of customers in China. Following recent changes in the Dutch regulations, advanced DUV [Deep Ultraviolet]-immersion is also now subject to license requirement.

The U.S. and Netherlands have, in other words, institutionalized their chokepoint power over ASML through export control regulation. Uncle Sam can exercise such power because ASML has substantial presence in the U.S. and is itself dependent on many key inputs manufactured in America. But the relationship goes deeper. As Miller describes in Chip War, the U.S. granted ASML access to advanced research from the Department of Energy in the 1990s to help develop EUV lithography.18 Granting such access to a foreign company — highly unorthodox — reflects the tremendous level of trust between both countries, who also closely cooperate on matters of intelligence, counterterrorism, and warfare.19

The Netherlands derives their chokepoint capability from the fact that ASML is a Dutch company and thus within their legal jurisdiction. The Dutch government can, in essence, apply export controls on ASML’s products whenever it pleases.20 This is a tremendous source of power. Much like the way the Dutch control the flow of water through their unmatched systems of dikes, dams, and floodgates, they can also control the flow of ASML’s exports to foreign buyers.

This represents a historical reversal of sorts. For 200 years, the Dutch East India Company aggressively expanded across the globe, using force to dominate the international trade of spice, sugarcane, and human beings. This was the primary source of Dutch sovereign power: encouraging a private company to expand outward and bring wealth inward. But now the country’s most important power is precisely the reverse: restricting the export of critical technologies.

Corporate Power (and its limits)

For ASML, this is annoying. The company wants to expand, and any restrictions on that expansion — particularly in enormous growth markets like China — likely inspire internal frustration.21 One might expect ASML to utilize its monopoly power as a source of leverage to push back on these restrictions. This would fit the narrative pushed by some IR scholars that corporate actors have supplanted nation-states as the world’s most important political actors.

But ASML’s options are limited. It is reliant on an incredibly complex supply chain that is largely within the jurisdiction of the U.S. and its allies. Important examples include Germany’s Zeiss and San Diego-based Cymer.22 Further, ASML, like most companies, is reliant on dollar-clearing facilities in the U.S. which America can choke-off through the use of sanctions. ASML cannot, in other words, simply pack up its things and move to Belarus to escape export controls. It is enmeshed in the Western-dominated cluster of economic networks — what Farrell and Newman refer to in a recent book as America’s Underground Empire.

This reflects an intriguing dilemma of corporate power. We normally assume that the world’s biggest companies are most capable of bending states to their will by, for example, threatening to relocate. But ASML exemplifies that supply chain complexity can have the opposite effect. In the context of great power competition, there appears to be an inverse relationship between supply chain complexity and the capacity of private actors to switch sides.

But what ASML can do is credibly threaten to relocate to another country within the U.S. sphere of influence. Existing reports have suggested that ASML may be interested in shifting substantial operations to France.23 The U.S. may not love this idea. Its dynamics with France are…different. Remember when America swooped in to steal a $60 billion submarine contract with Australia?24 Whoops! But when it comes to ASML, America’s primary concern is upholding export controls vis-à-vis China and other adversaries. And there is little risk that France would fail to support this goal if ASML started manufacturing EUV lithography systems in la République.

Lost Leverage

For the Netherlands, however, this would be a geopolitical disaster. The Dutch have one of the world’s most modern militaries and an enormously important intelligence service.25 And, of course, the Netherlands is the home of international law, hosting both the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court. But its greatest power is arguably more subtle: its ability to control the most important hub in global microchip production.

To understand the importance of ASML, one need only look at China’s desperate efforts to create a competitor in the form of Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment (SMEE). China wants to become self-sufficient in chip production, and it cannot do so while ASML retains its monopoly. Thus it is no surprise that ASML is a target of espionage. The company has reported theft of intellectual property by at least one Chinese employee.26 And though ASML has publicly rejected speculation of a tie to the Chinese government, it nevertheless acknowledges in its annual report that industrial espionage is a key security risk.27

Losing ASML would, therefore, deprive the Netherlands of the power to control the flow of critical technology to foreign adversaries. This is currently a black and white issue in the sense that certain actors — China, Russia, North Korea — simply cannot be allowed to import the world’s most important machine. But there are (and likely will be in the future) many grey areas where the Netherlands can employ its export controls as a source of leverage in negotiations.28 This includes negotiations with its allies. The looming U.S. election has forced European countries to consider how they might deal with an American autocrat. Retaining the capacity to control ASML would, for the Netherlands, be a sensible first step.

Here’s a video with rock music which would normally be an opportunity to make a joke but here it’s just completely justified.

ASML, Busting ASML Myths (this one is true).

The science behind it is, of course, the work of many brilliant scientists not necessarily affiliated with ASML.

Toby Sterling, Dutch government scrambling to keep ASML in Netherlands.

Ibid.

Charlotte Van Campenhout and Toby Sterling, ASML's threat to leave uncovers deeper concerns in Netherlands Inc.

Similarly discussed in the context of legal extraterritoriality by Anh Nguyen, The Discomfort of Extraterritoriality: US Semiconductor Export Controls and why their Chokehold on Dutch Photolithography Machines Matter.

Henry Farrell, Abraham L. Newman; Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion. International Security 2019; 44 (1): 56.

Alexandra Alper, Toby Sterling and Stephen Nellis, Trump administration pressed Dutch hard to cancel China chip-equipment sale - sources.

Ibid.

ASML Annual Report 2023, p. 58.

Chip Wars, p. 187.

One small example: Dutch intelligence first to alert U.S. about Russian hack of Democratic Party. It also, as Miller notes, reflected desperation: there was no American company that was positioned to use such research as effectively.

Albeit subject to two important caveats: (1) domestic legality and (2) the Netherlands can only push so hard before ASML might consider relocating. There is a delicate balance here between geopolitical goals and upsetting the company.

While not about ASML specifically, a recent article by Ling S. Chen and Miles M. Evers corroborates that American chipmaking companies lobbied against economic conflict with China to avoid profit disruption.

Cheng Ting-Fang, ASML says decoupling chip supply chain is practically impossible.

ASML Annual Report 2023, p. 168.

Within limits, of course, as choking too hard could encourage ASML to more seriously considering relocating.