Replaceable Parts

The Netherlands has become a central hub for sustaining the world's most advanced fighter jet. But centralization is not without its risks.

In the municipality of Woensdrecht, a sleepy corner of the Netherlands not far from the Belgian border, lies a seemingly unremarkable warehouse. It is surrounded by trees planted in perfectly straight lines. And sitting across the street is a stale office park with car dealerships and a pet food distributor. But the Woensdrecht Logistical Center is not just any warehouse. To the contrary, this privately-operated depot is an integral strategic military hub, one that is essential to the capacity of the U.S. and its allies to maintain air superiority in Europe. And the reason why can be summarized with one simple phrase: F-35.

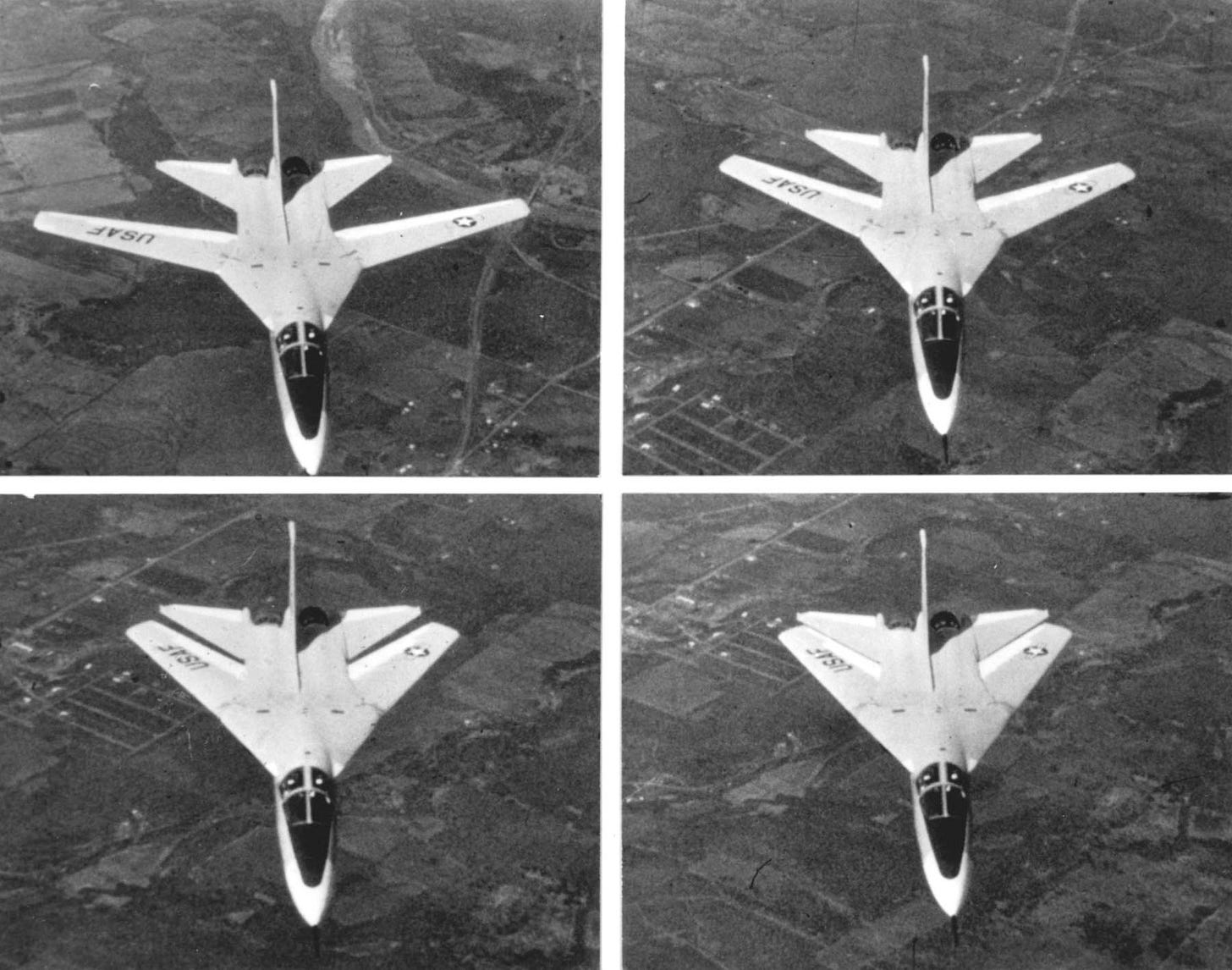

The F-35 is the world’s most advanced fighter jet. It can travel at supersonic speed (1,200 miles per hour) even when fully fueled and armed.1 But what really sets the F-35 apart is its technology. The jet is coated with radar-absorbent material and can release a transmitter mid-flight to disrupt tracking algorithms and serve as a decoy for enemy missiles.2 It also features six infrared cameras around the aircraft to create a full ‘sphere’ of situational data on threats. That information is transmitted to the digital interface of the pilot’s helmet, allowing them to ‘see through’ the plane at any angle.3 The helmet system alone costs $400,000.4 But this is peanuts compared to the $80-100 million necessary to buy the full plane.5

Even this figure, however, is an underestimate. It only represents the ‘flyaway’ cost: the basic production of the unit.6 There are also ‘sustainment costs’ to operate the jets in practice. This includes things like training, simulators, software, energy, and the costs of pilots and support personnel.7 One analysis suggests that when these factors are considered the real cost per plane is more like $117-164 million.8

And, indeed, there is one aspect of sustainment that often flies under the radar: the maintenance of spare parts. The F-35 is composed of 300,000 parts manufactured by more than 1,700 individual suppliers.9 That’s a lot to keep track of. What do you do when parts need replacing? You probably don’t want to keep a full set of spares for each plane at every base and aircraft carrier. That would be…expensive. Particularly given that the U.S. and its allies will eventually operate hundreds of F-35s from bases located all over Europe.10 But you also want to avoid the headache of having every base separately order parts from thousands of individual suppliers.

Enter the Woensdrecht Logistical Center. This Center serves as the centralized depot of spare parts for all F-35s operating in Europe.11 And the company overseeing the depot, OneLogistics, is responsible for coordinating the distribution of those parts to wherever they are needed.12 This is a sensible solution. And it is another example of a Dutch company serving as a key ‘hub’ in the industrial networks of Western military power. In a previous post, we discussed ASML, a Vendhoven-based company which sits at the nexus of advanced microchip production. OneLogistics, located just an hour away by car, plays a similarly central role in F-35 sustainment. The Dutch have a way of making themselves essential.

But centralization creates its own operational risks. In February, three human rights organizations successfully petitioned the Hague District Court to stop the Netherlands from exporting F-35 spare parts to Israel.13 And the state is now lodging an appeal in the Dutch Supreme Court.14 The case exemplifies a clash between international legal principles and foreign policy objectives. And it demonstrates that centralized ‘hubs’ in supply chain networks are not always a source of power for states. They can also be sites of strategic vulnerability.

The Need for Speed

It was far from inevitable that Woensdrecht would become the European hub for F-35 sustainment. But a hub was needed somewhere. Sustainment tends to account for more than 60% of aircraft costs over their lifetime.15 And those costs have ballooned to historic proportions for the F-35 program. By May 2024, the program had delivered 990 aircraft to the U.S. and its allies.16 But this milestone was supposed to have been achieved more than 10 years ago. And the program is currently $209 billion over budget.17 To understand how we arrived to this point, we have to go back in time. Specifically, to the early 1960s, when newly elected President John F. Kennedy appointed Robert McNamara as his Secretary of Defense.

One of McNamara’s first actions as Secretary was to launch the so-called Tactical Fighter Experimental, or TFX, program. The purpose of the program was to address the perceived inefficiency of having every branch of the military develop their own lines of aircraft.18 Why not save costs by creating a single fleet which can serve, say, both the Air Force and Navy? This type of thinking was typical of McNamara. After a short stint as a business professor, he served in World War II as a statistical officer working on operational planning.19

But the TFX program was a catastrophe. Both the Air Force and Navy resented the imposition of unilateral control over their aircraft selection.20 And McNamara made things worse by overruling the leadership of both branches on the selection of the contractor. The $7 billion project — an incredible sum in the early 1960s — went to General Dynamics rather than Boeing.21 The project was plagued by delays, inflated costs, and disagreements on the specifications of the proposed aircraft.22 Eventually the Navy decided to drop out entirely. This left only the Air Force to take delivery of the newly created fleet of F-111 fighter jets. But despite the failure of the TFX project, the dream of achieving efficiency gains through the creation of a harmonized fleet was not killed. It was just delayed.

In the 1990s, the U.S. military revisited the idea of creating a common fleet of aircraft which could be used across branches. But this time the ambition was even greater. Why stop at the branches of the American military? Why not create a class of fighter jets that can also be used by Western allies? The potential costs savings would be enormous. Imagine a world where NATO allies fly a common fleet of jets which can be serviced at any air base in Europe. Everyone would work from the same manual and use the same spare parts. The IKEA of lethal air power.

This was, in essence, the goal of the Joint Strike Fighter program.23 Launched in 1993, the JSF is a unique experiment in international military cooperation. It centers on the creation and sustainment of the F-35 fleet. But unlike most military aircraft projects, these costs are shared by a consortium of allied states. Each state’s contribution is roughly equivalent to the number of F-35s they anticipate purchasing.24 The U.S. is by far the biggest partner (and, as a result, the biggest investor) in the program with a planned order of 2,470 aircraft.25 This is more than twice the number of F-35s ordered by every other partner nation combined.26

Nevertheless, the U.S. can use all the help it can get. The program has been plagued by operational challenges and cost inflations reminiscent of its predecessor from the 1960s, the TFX.27 The total cost of the F-35 program is now projected to exceed an astounding $2 trillion.28 And approximately 79% of those costs are attributable to operations and sustainment.29 This includes the ever-rising costs of maintaining a global supply chain for the delivery of F-35 spare parts.30

Thus it is no surprise that the U.S.-led coalition has sought opportunities to improve logistical efficiency. In 2017, the Department of Defense took a major step toward that goal by creating two regional hubs for F-35 spare part distribution.31 One regional hub, centered on Asia, was assigned to Hunter Valley, Australia, an area better known for its wineries.32 And for spare part distribution in Europe, it was decided that all roads would lead through one location: Woensdrecht.

Creating a Hub

The Netherlands was deeply involved in the JSF program long before it was selected as Europe’s regional hub. As one of the program’s “Level 2” partners (alongside Italy), the Netherlands made a sizeable financial contribution despite domestic political concerns about its costs.33 This allowed the Netherlands to have some input on the design of the F-35, including making the cockpit larger to accommodate taller Dutch pilots.34 But more important were the ancillary benefits, commercial and otherwise, of playing a significant role in the global F-35 infrastructural network. As Giles Scott-Smith and Max Smeets summarize:

…it will allow the Netherlands to continue to play a key role in international security, while at the same time securing a competitive industrial infrastructure and cutting-edge research and development capability for its aerospace sector and the wider “knowledge economy” that surrounds it. These capabilities are tied strongly to Dutch national pride.35

And if there is one company which personifies these benefits, it is OneLogistics. This is a remarkably small company of only 10 staff.36 So small, in fact, that the CEO hosts the corporate promotional videos on his personal Youtube channel, alongside a Comedy Central-style roast of a co-worker.37 But don’t be fooled: this is one of the most important companies you’ve never heard of.

OneLogistics acts as the ‘control tower’ overseeing F-35 sustainment throughout Europe. This includes managing the Woensdrecht Logistical Center, a 14,000 square meter depot operated by more than 900 Dutch Air Force personnel.38 OneLogistics coordinates these processes from above, keeping track of the hundreds of thousands of spare parts which arrive to Woensdrecht and are subsequently distributed to F-35 partners. Equally important, the company handles the customs and tax complications of moving sensitive military equipment between dozens of jurisdictions.

The creation of the Woensdrecht hub is a major win for the U.S.-led coalition of F-35 partners. It provides a centralized depot through which spare parts can be efficiently distributed to bases in Europe and the Middle East. And it is also a major win for the Netherlands. It establishes the country as an integral ‘node’ in the industrial supply chain network of the world’s most advanced fighter jet. And these types of decisions tend to be self-reinforcing. The Logistical Center was, for example, recently enhanced to perform on-site maintenance of F-35 aircraft39 With every enhancement to the hub, the network’s reliance on Woensdrecht grows. The depot for replaceable parts is, in other words, becoming increasingly irreplaceable.

Centralization does, however, create its own types of risks. The Woensdrecht Center would be an obvious target in a direct military confrontation, one whose destruction could be debilitating for NATO air power. But there are more subtle risks posed by the location itself. Hubs are not created in a vacuum. They are embedded in a wider social environment which may seek to impose limitations on their use. And one particularly relevant counterbalancing force in the Woensdrecht case is the legal environment in which the hub is located.

The Netherlands is bound by EU and UN Treaty law surrounding the export of military goods.40 The same is true of most European countries. But the Netherlands is unique in its commitment to international law. It is, of course, the home of both the ICC and the ICJ.41 And it features a ‘monist’ legal system in which international law generally applies as if it were domestic law.42 The country’s commitment to international law is so strong, in fact, that is constitution prescribes that the Dutch armed forces will not just protect the Kingdom but also “maintain and promote the international legal order.”43 And unlike some EU states, like Hungary, it features one of the world’s most open and accountable systems for bringing disputes.44

These are very good things! But from a purely strategic perspective, it also presents a type of operational risk for F-35 partners. There is a reason the U.S. maintains a prison in Guantánamo Bay. It allows the state to operate without the limitations imposed by its own domestic legal system (let alone international law).45 But by centralizing F-35 sustainment in the Netherlands, the U.S.-led coalition has made itself dependent on a hub that is much more vulnerable to legal challenges, challenges which could impose limitations on the entire supply chain network. And that operational risk became real when F-35s were deployed in the Gaza Strip.

Hub Dynamics

In 2016, Israel became the first Middle Eastern nation to receive the F-35.46 Israel has historically sourced spare parts from the Woensdrecht Logistical Center, which is the closest regional depot.47 But that relationship came under new scrutiny when Israel celebrated the use of F-35s in Gaza.48 Three human rights organizations took the Dutch state to court, kicking off a legal battle over whether the state should continue to facilitate the (re)export of spare parts to Israel.49

In highly simplified terms, the case centered on whether the Dutch Minister of Foreign Trade had adequately reviewed the risk that spare parts shipped to Israel might be used in ways that violate international humanitarian law.50 The answer, according to the Hague Court of Appeal, was no:

Now that Israel's war actions in the Gaza Strip have involved a clear risk of serious violations of humanitarian law and the F-35s have been deployed in support of those war actions, there is a clear risk that the F-35 parts to be exported will be used in committing serious violations of international humanitarian law.51

The Court subsequently ordered the Netherlands to cease all export or transit of spare parts where Israel is the ultimate final destination.52 Like an economic sanction, the Court rendered the Israeli state persona non-grata, cutting off their access to the Woensdrecht global distribution system.

But, also like an economic sanction, the ban was immediately met with efforts to circumvent its restrictions. Dutch news service NOS has reported that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has considered potential alternative solutions, including the possibility of issuing new export permits which are conditional on Israel promising not to use spare parts in Gaza.53 What has garnered more attention, however, is the complaint made by the same human rights organizations that Woensdrecht continues to indirectly export spare parts to Israel through the U.S.54

The court did not deny that this is a possibility.55 But it concluded, in simplified terms, that the Dutch government should not be penalized for routes taken by spare parts after they leave the Netherlands.56 Here, one again, there are echoes of economic sanctions. We have previously discussed how dual-use goods are making their way to Russia by being re-exported through third countries. It would be…ironic…if the same mechanism was being employed to indirectly supply spare parts to Israel.

But the ironies do not stop there. We normally view hubs as a source of power for states. The basic idea is that states who control central hubs in the world economy, like datacenters or pipeline crossings, can leverage that control to their strategic advantage.57 Some have even suggested we are in the midst of a second Cold War, one characterized by a battle between the U.S. and China for centrality within these infrastructural networks.58

What the Woensdrecht Affair demonstrates, however, is that hubs can also be sites of strategic vulnerability.59 These hubs do not exist in a vacuum. They are embedded in legal regimes which govern their relationship with the state. In some cases, those rules may support the state’s capacity to exercise control. Weak privacy protections in the U.S., for example, support the government’s ability to surveil telecommunications data held in centralized hub datacenters.60 But in other scenarios, like Woensdrecht, the legal environment can invite countervailing forces which limit the state’s capacity to utilize the hub toward its own strategic objectives.

This, of course, is not a bad thing. The whole point of international law is to impose limitations on states. And it is obviously positive that the Netherlands possesses a legal environment which keeps the state accountable — particularly in matters of war and human rights. But for those who would wish for the state to be unencumbered by such concerns, there is a Machiavellian lesson lurking just beneath the surface. And that lesson is simple: be careful where you centralize.

F-35: Unrivaled capabilities.

Jonathan H. Kantor, Here’s what makes the F-35 helmet so unique.

The costs are complicated.

Per the U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency, flyaway costs are “The costs related to the production of a usable end item of military hardware. Flyaway cost include the cost of procuring the basic unit (airframe, hull, chassis, etc.), a percentage of basic unit for changes allowance, propulsion equipment, electronics, armament, and other installed government-furnished equipment, and nonrecurring production costs. Flyaway cost equates to rollaway and sail-away costs.”

Dan Grazier, Selective Arithmetic to Hide the F-35’s True Costs.

Stephen Losey, Pentagon suspends F-35 deliveries over Chinese alloy in magnet.

Per Lockheed Martin.

Ibid.

Court proceedings (in Dutch).

Agripino et al., A Lean Sustainment Enterprise Model for Military Systems, 276.

United States Government Accountability Office, Program Continues to Encounter Production Issues and Modernization Delays, 1.

Ibid.

George M. Watson Jr. and Herman S. Wolk, "Whiz Kid": Robert S. McNamara's World War II Service.

Ibid Note 17.

Ibid.

Ibid; Paul Bevilaqua, Inventing the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

There were definitely some other goals…but this is the one I’m focusing on.

Netherlands Court of Audit, The financial aspects of participation.

Department of Defense, 2023 Modernized Selected Acquisition Report (MSAR) F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) Program (F-35), 55-56.

Ibid.

Joseph Trevithick and Tyler Rogoway, How The F-35’s Lack Of Spare Parts Became As Big A Threat As Enemy Missiles.

F-35 Joint Program Office, DoD Announces F-35 Global Warehousing Assignments.

Australian Government, Hunter Valley on Track to Become Regional F-35 Aircraft Sustainment Hub.

Giles Scott-Smith & Max Smeets, Noblesse oblige: The transatlantic security dynamic and Dutch involvement in the Joint Strike Fighter program.

Ibid.

Ibid, 67.

Rene de Koning, F35 component logistics English Internet Mix DEF REV.

Defence Industry Europe, Netherlands opens F-35 maintenance facility at Woensdrecht Air Base.

León Castellanos-Jankiewicz, Dutch Court Halts F-35 Aircraft Deliveries for Israel.

That’s International Criminal Court and International Court of Justice.

Evert A. Alkema, Netherlands. See also Harry H.G. Post, International Criminal Law: Reflections on Dualism and Monism. There’s a ton of subtleties I’m not covering here (nor am I qualified to do so!).

Rule of Law Index, Netherlands.

See, e.g., Johan Steyn, Guantanamo Bay: The Legal Black Hole.

Lockheed Martin, Israel's 5th Generation Fighter.

Though Israel has reportedly taken some steps to develop independent sustainment and maintenance capabilities, such as domestically-developed software improvements.

Frank Kuhn und Elisabeth Hoffberger-Pippan, Court Orders Dutch Government to halt the Export of F-35 Parts to Israel: Implications for the War in Gaza and Beyond.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Much of this discussion is inspired by Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman’s concept of weaponized interdependence.

As Marieke de Goede and Carola Westermeier have written, “Infrastructures are not passive sites to be used in the service of preexisting hegemonic power but can themselves route, block, challenge, or rework power.”

Covered in Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman’s Underground Empire.